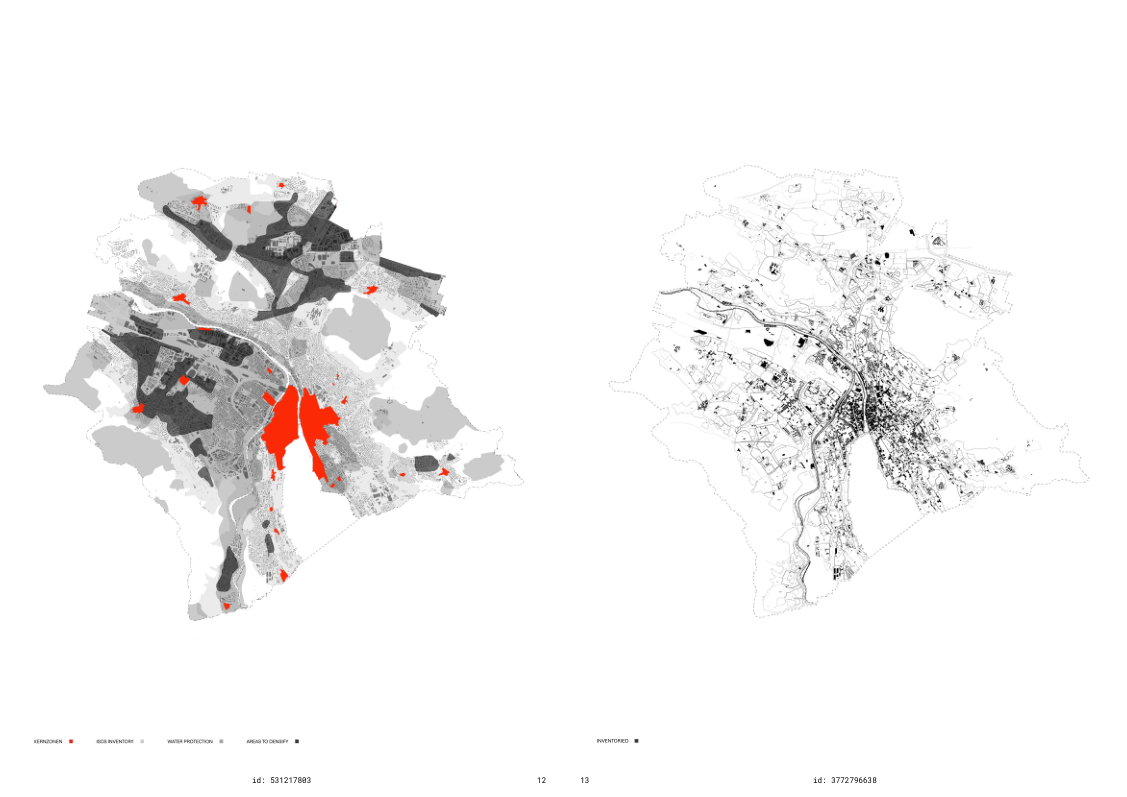

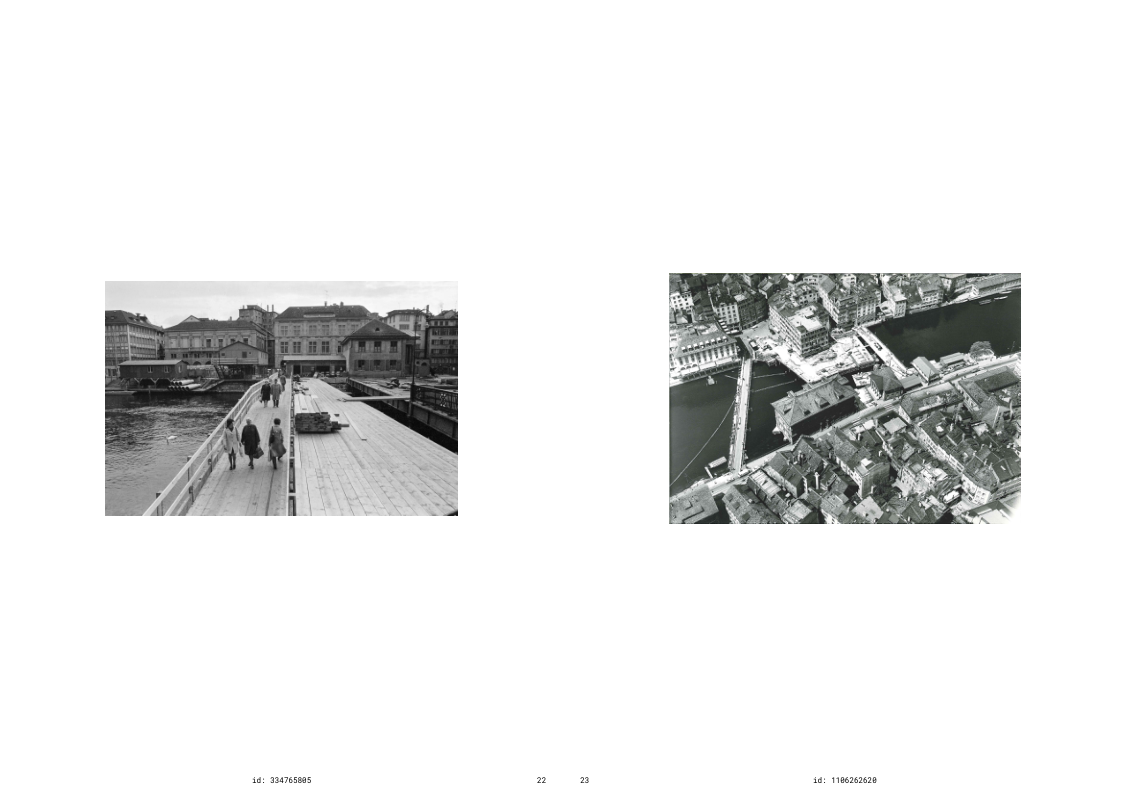

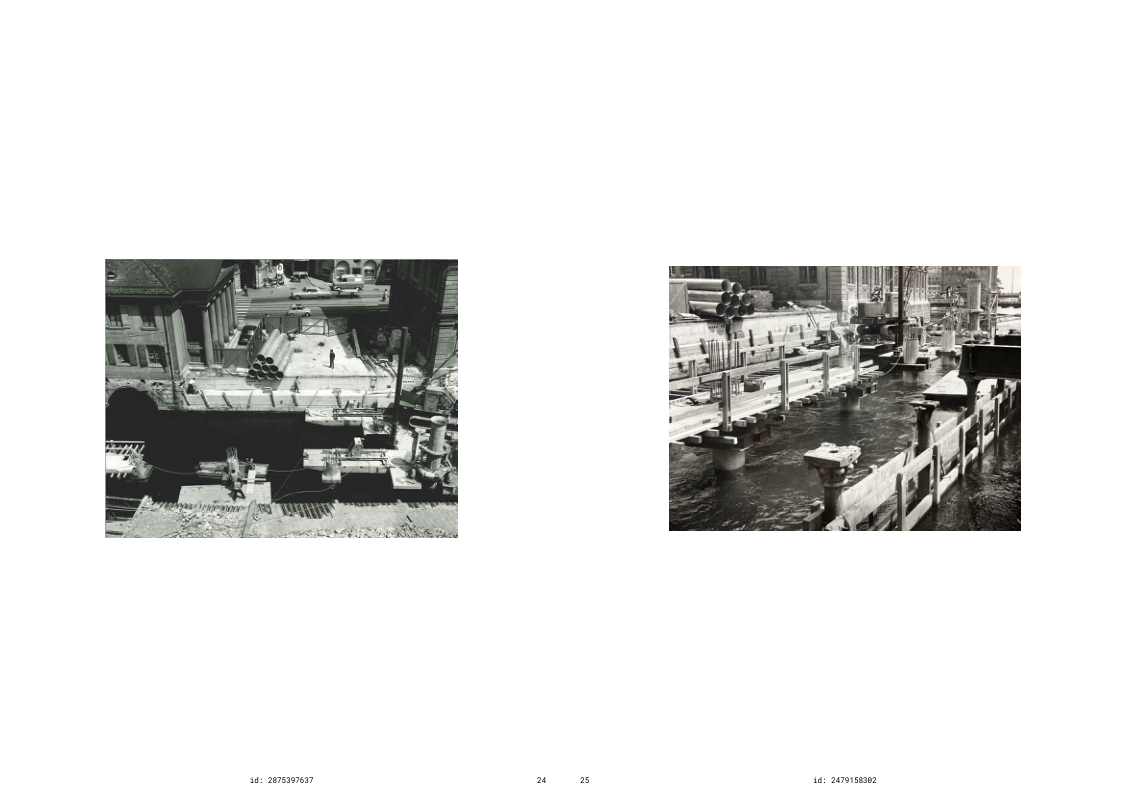

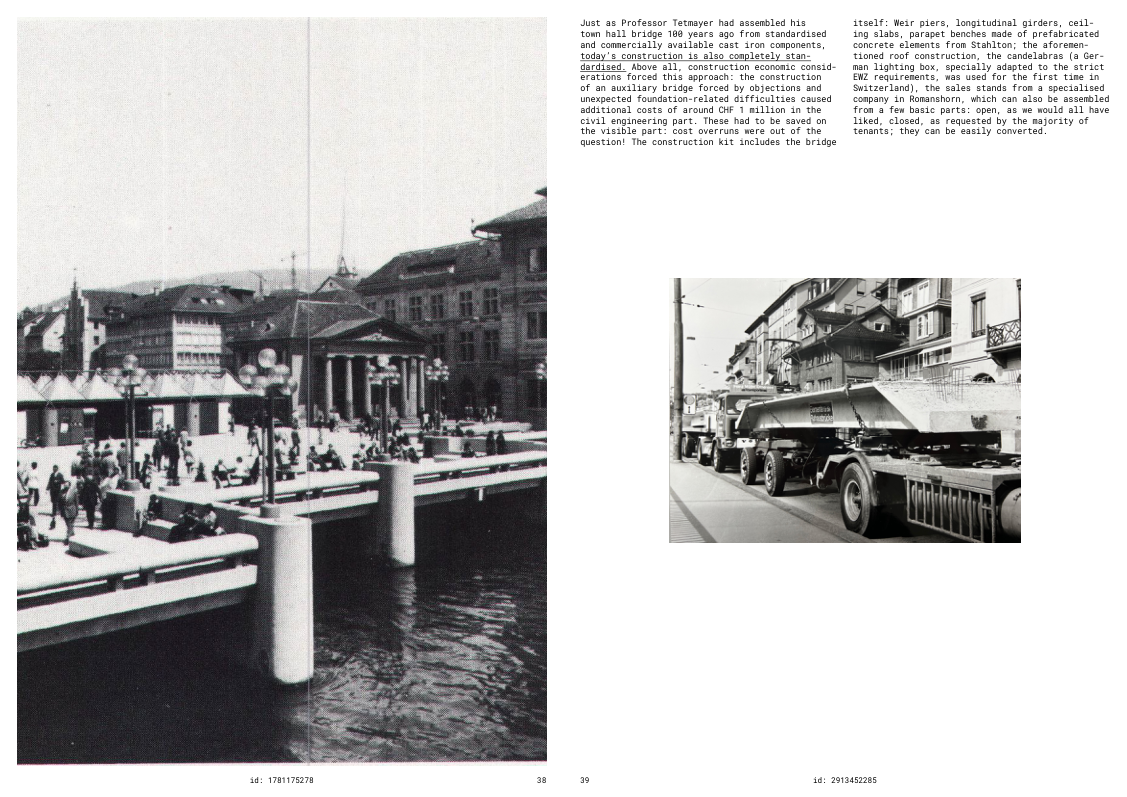

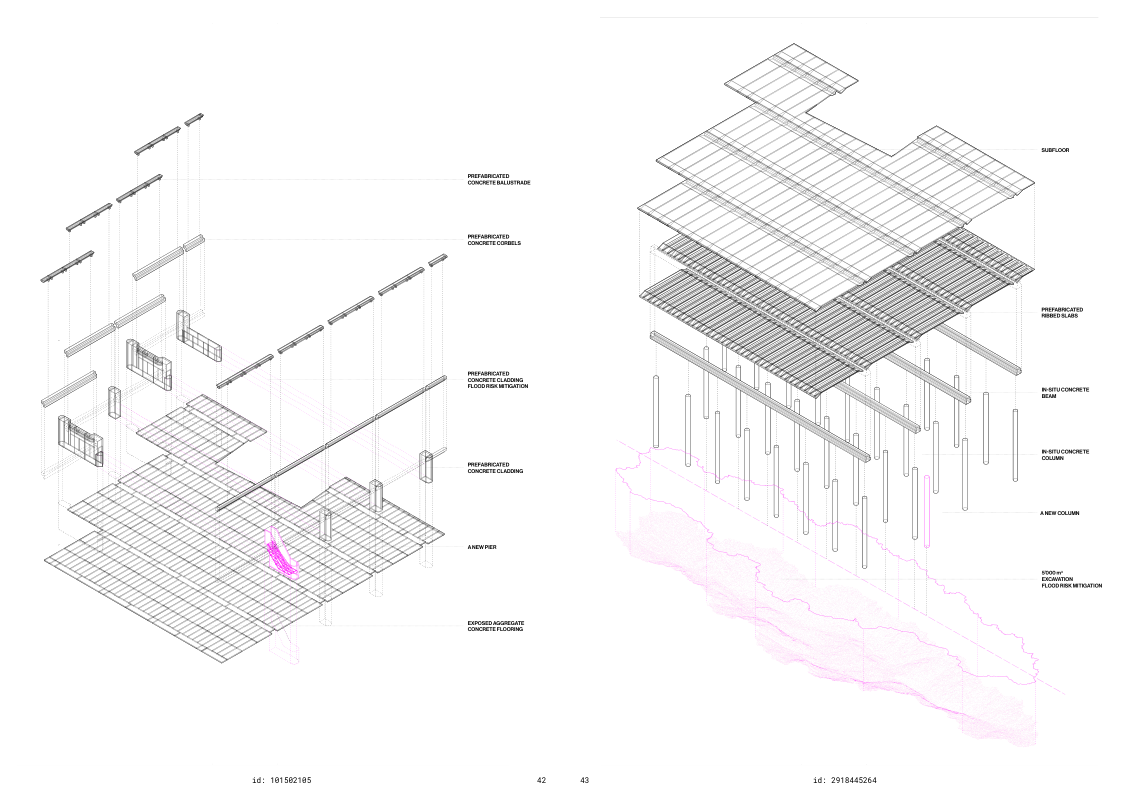

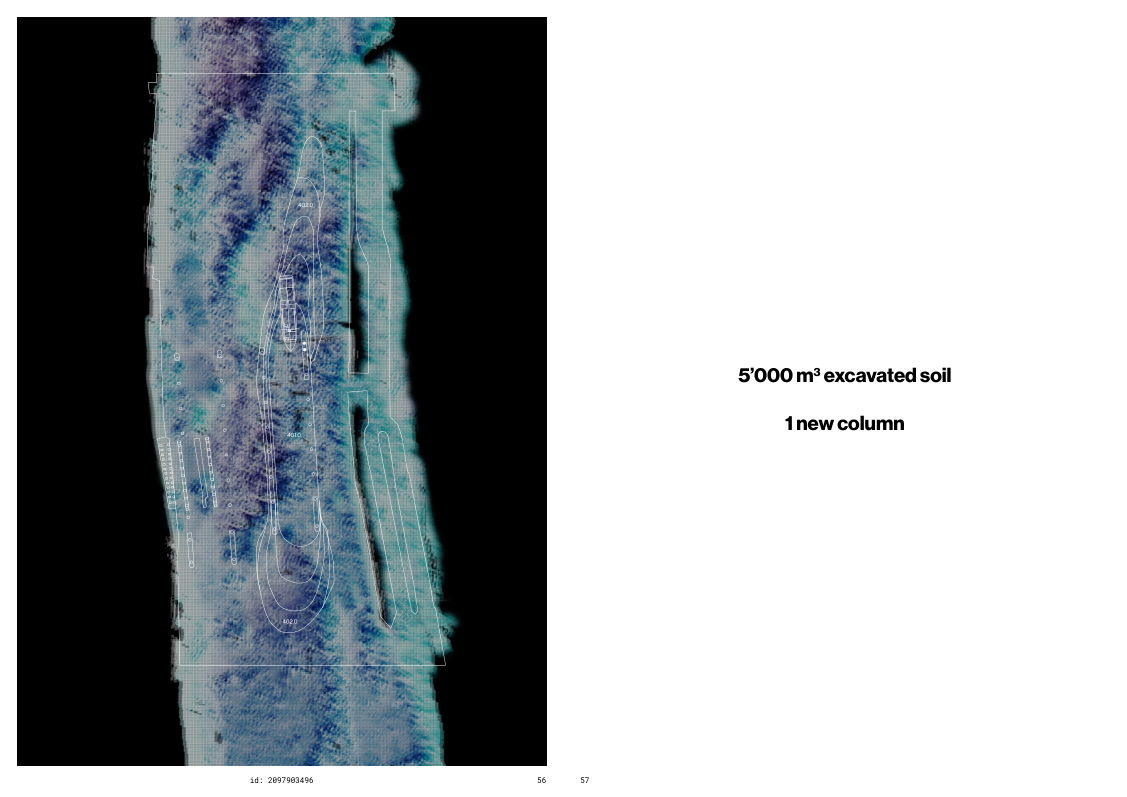

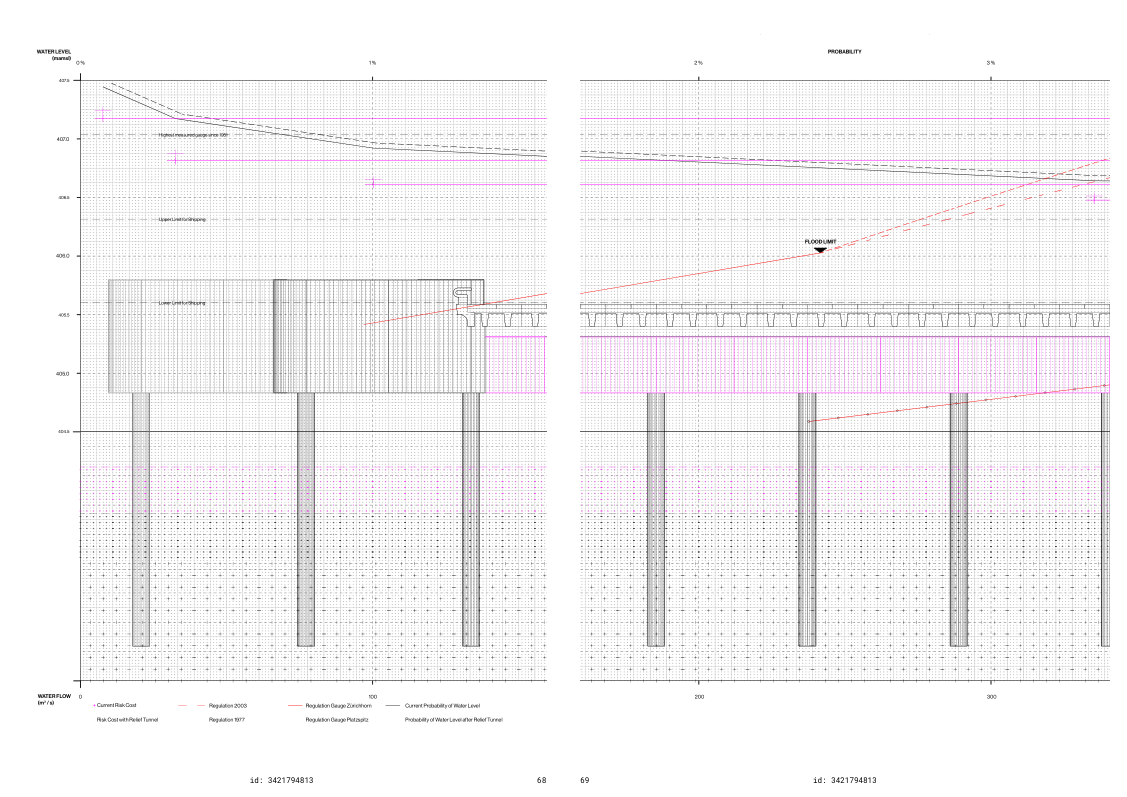

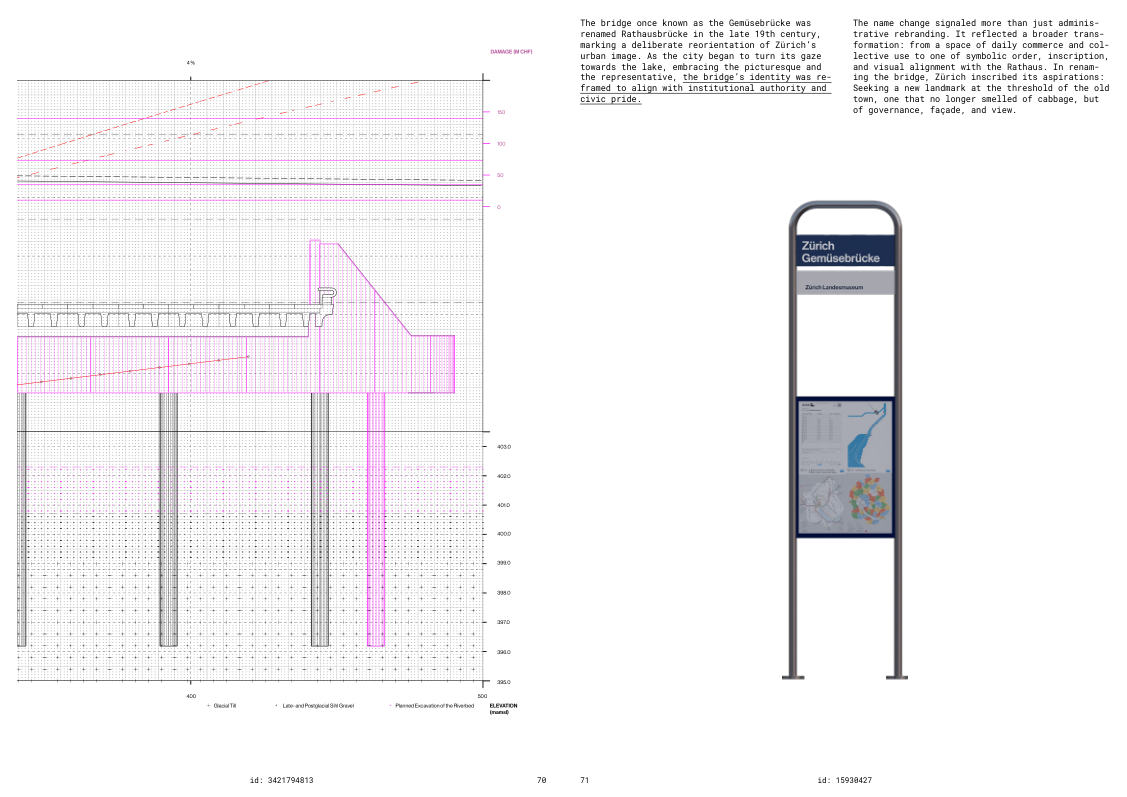

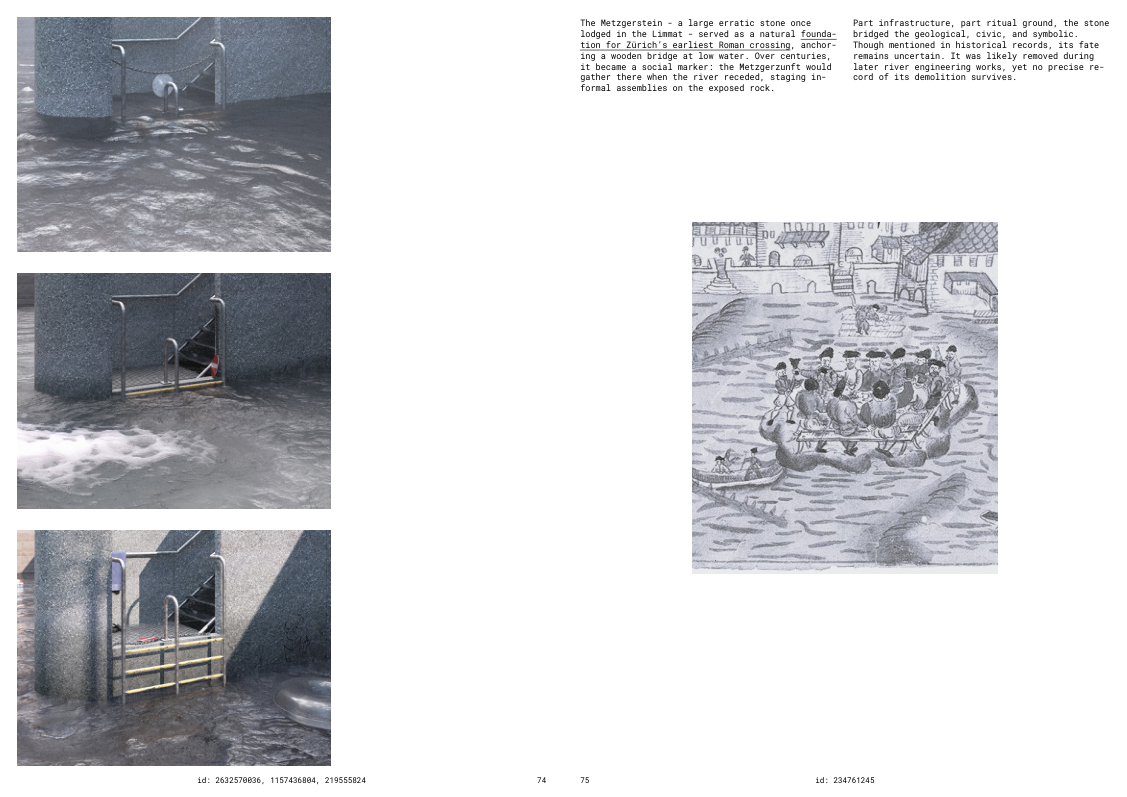

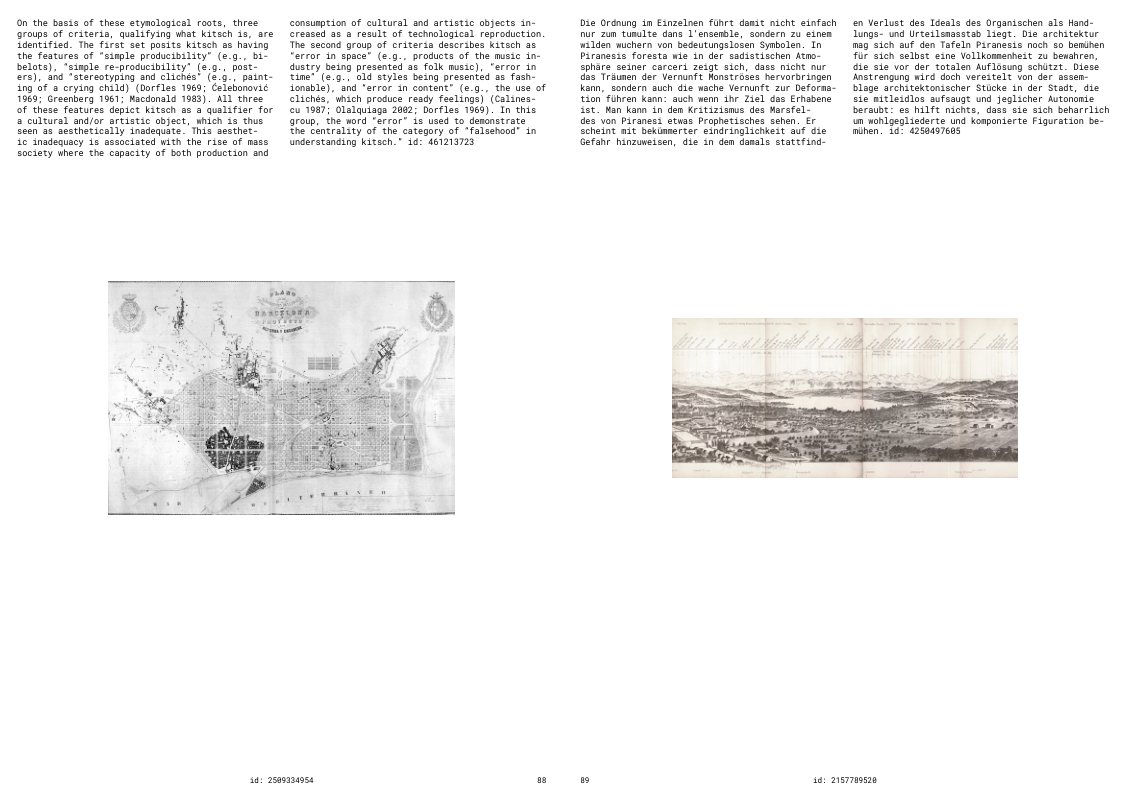

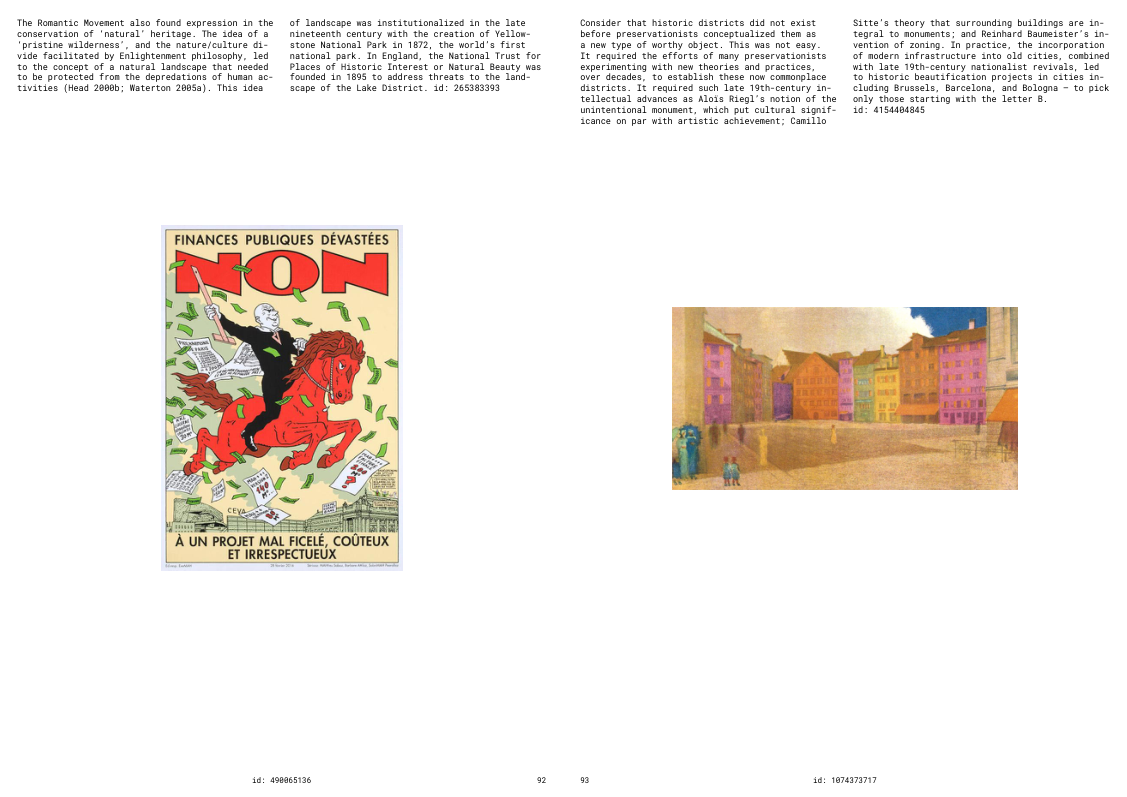

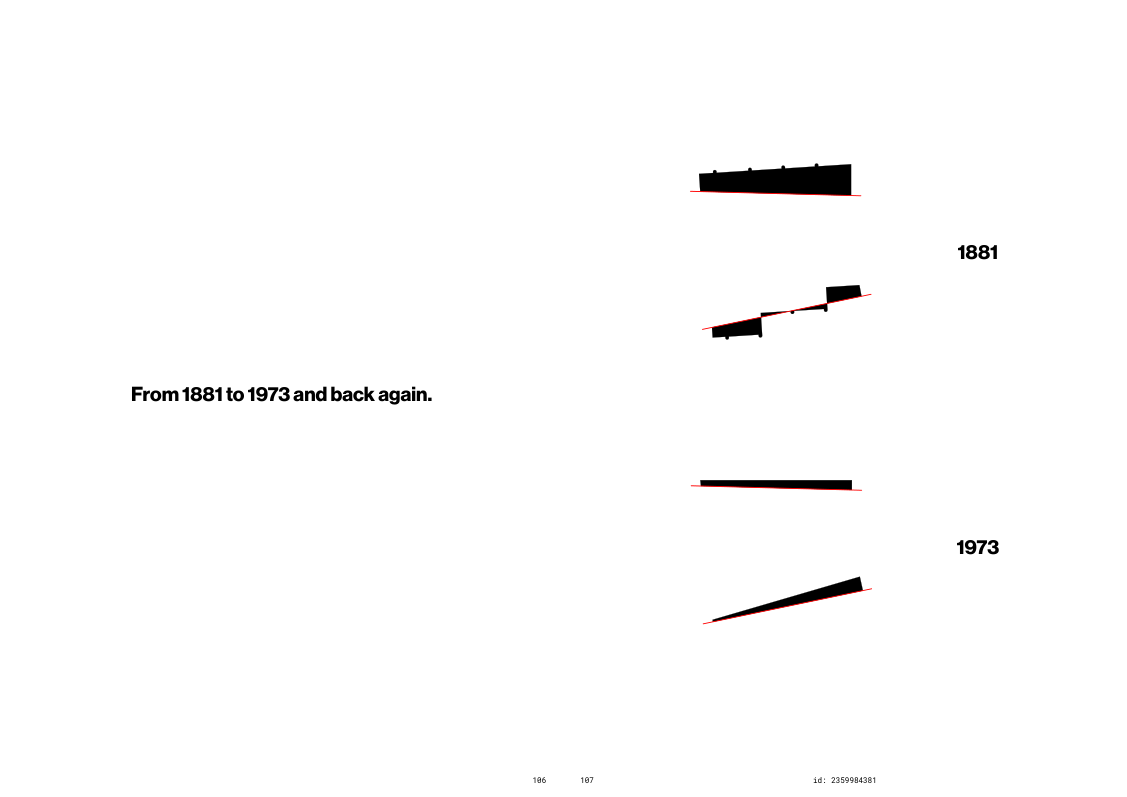

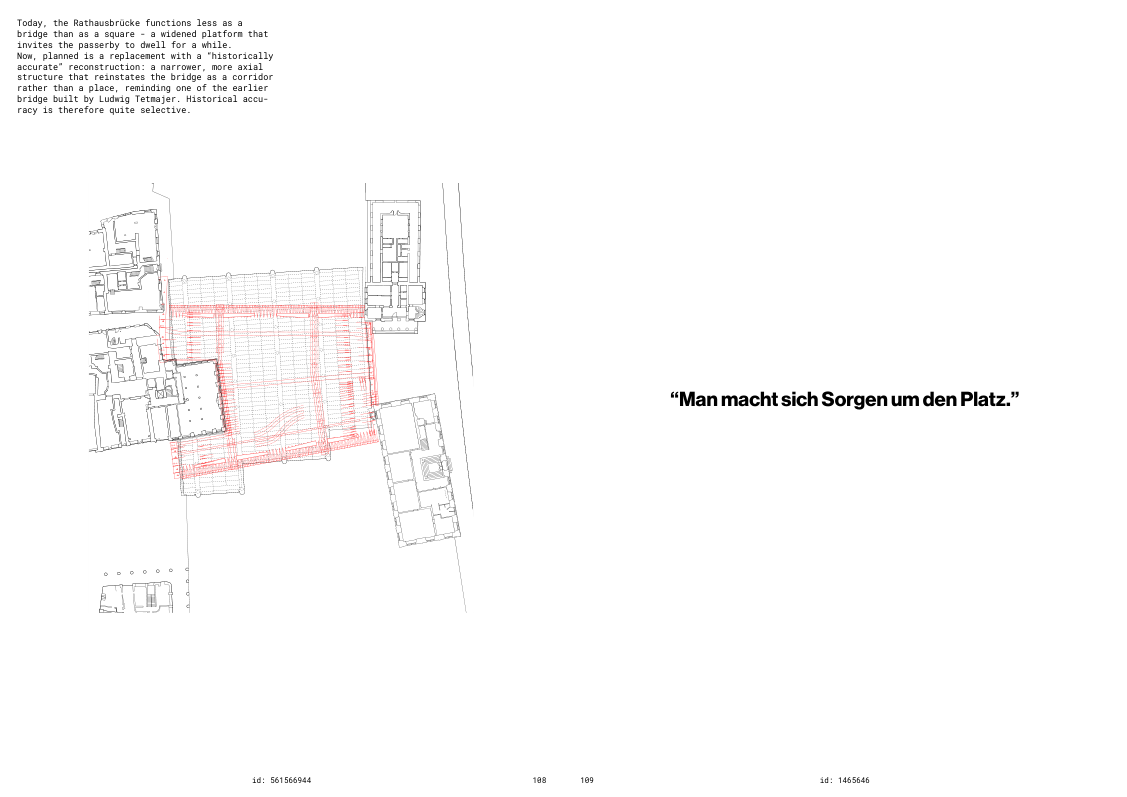

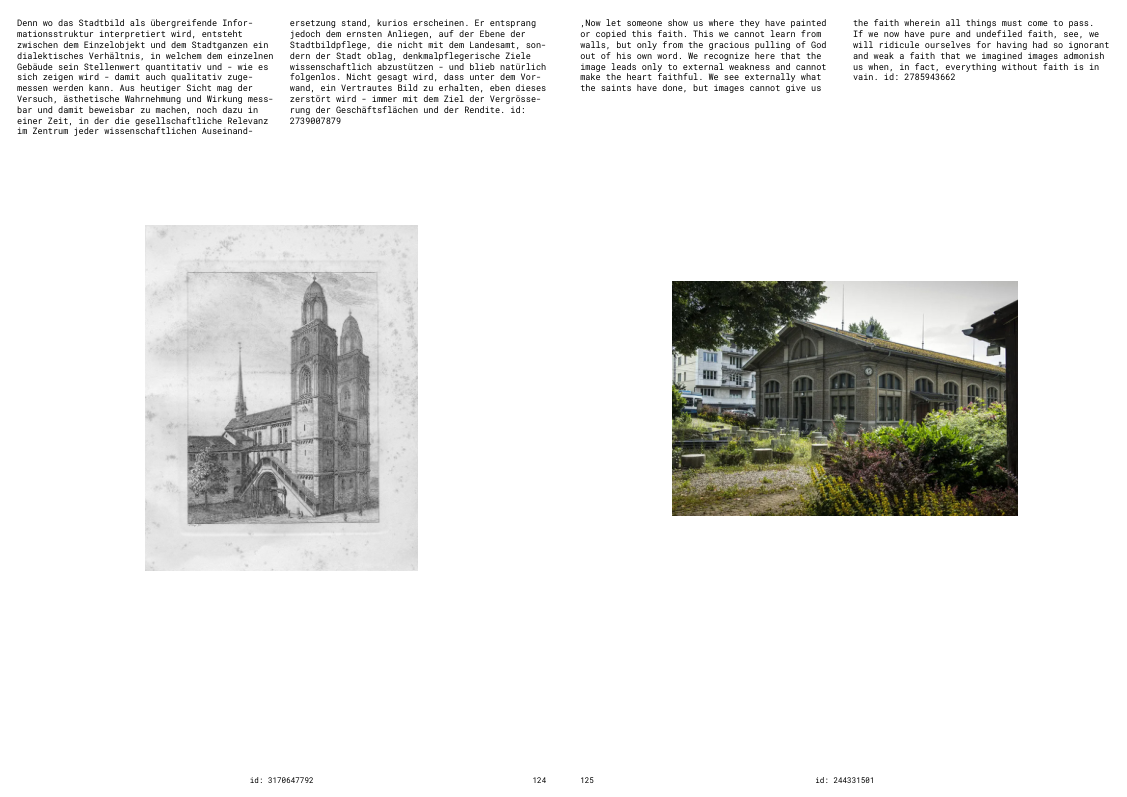

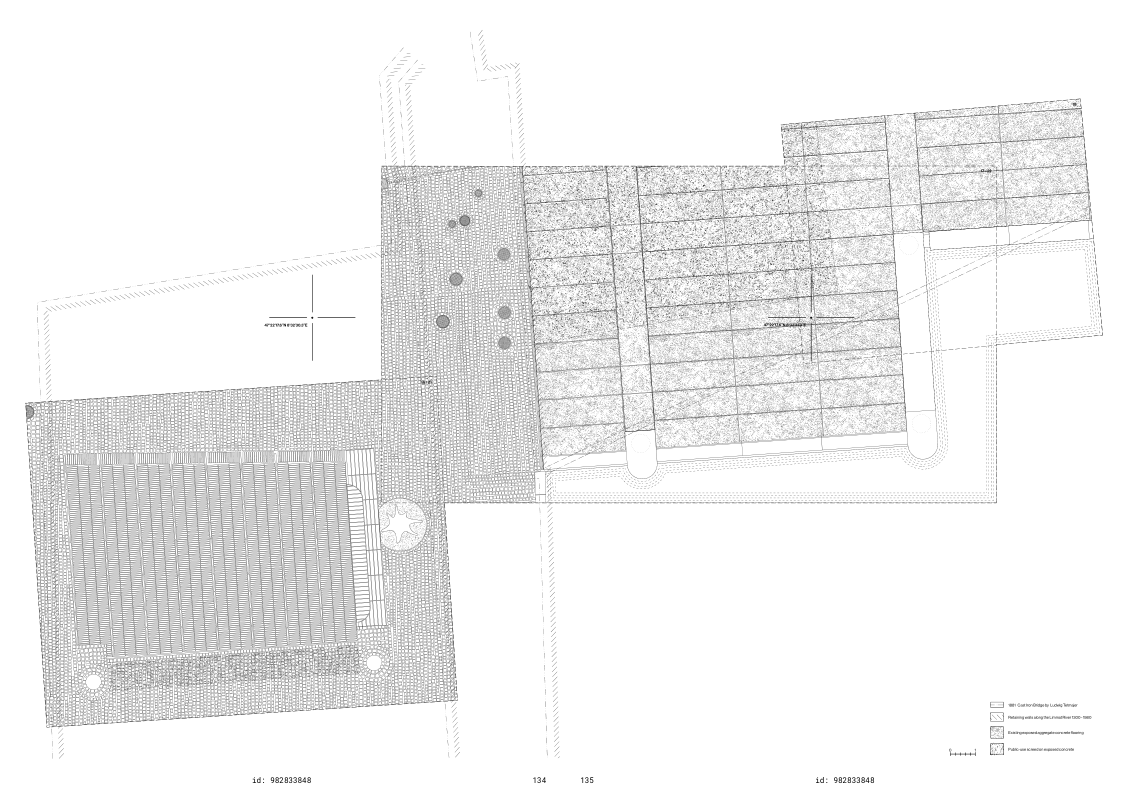

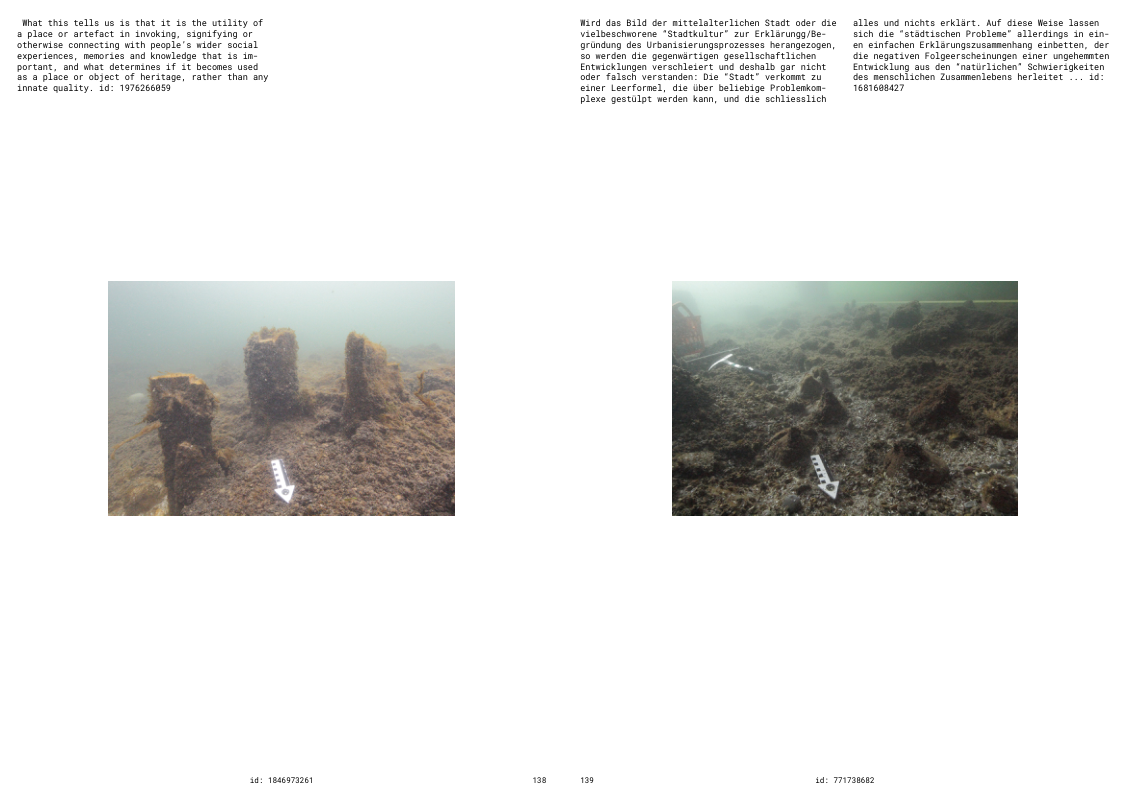

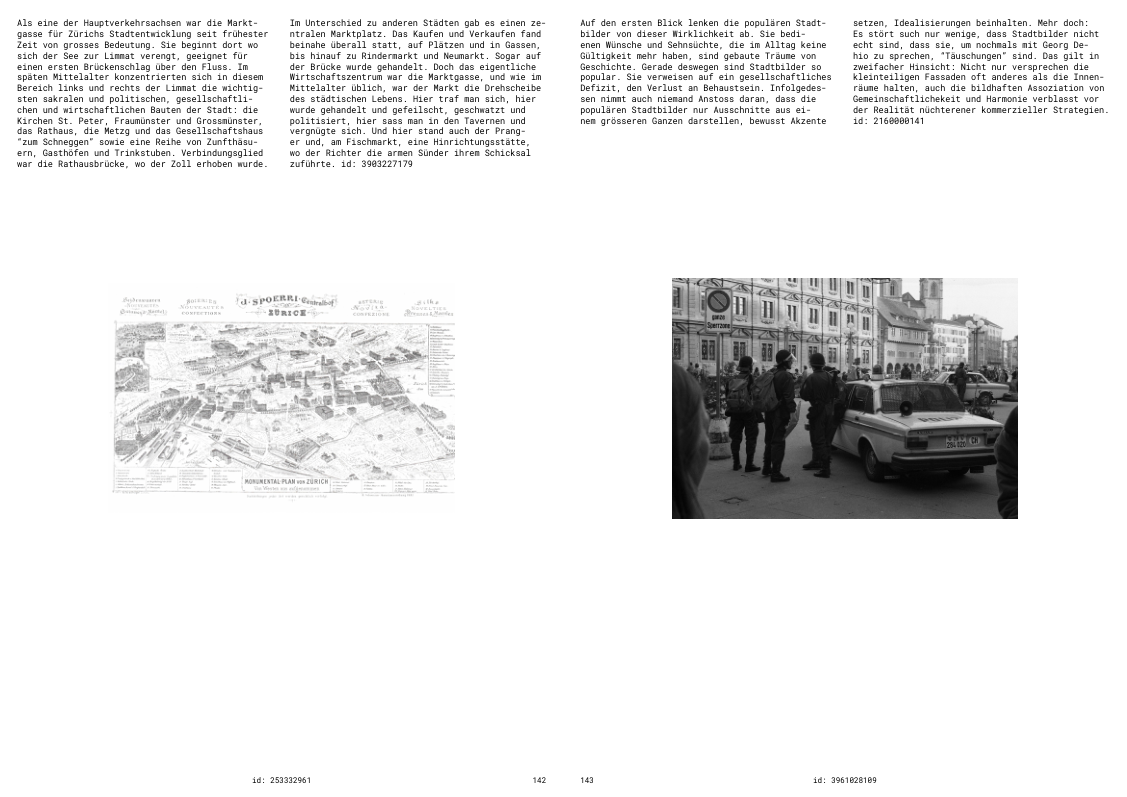

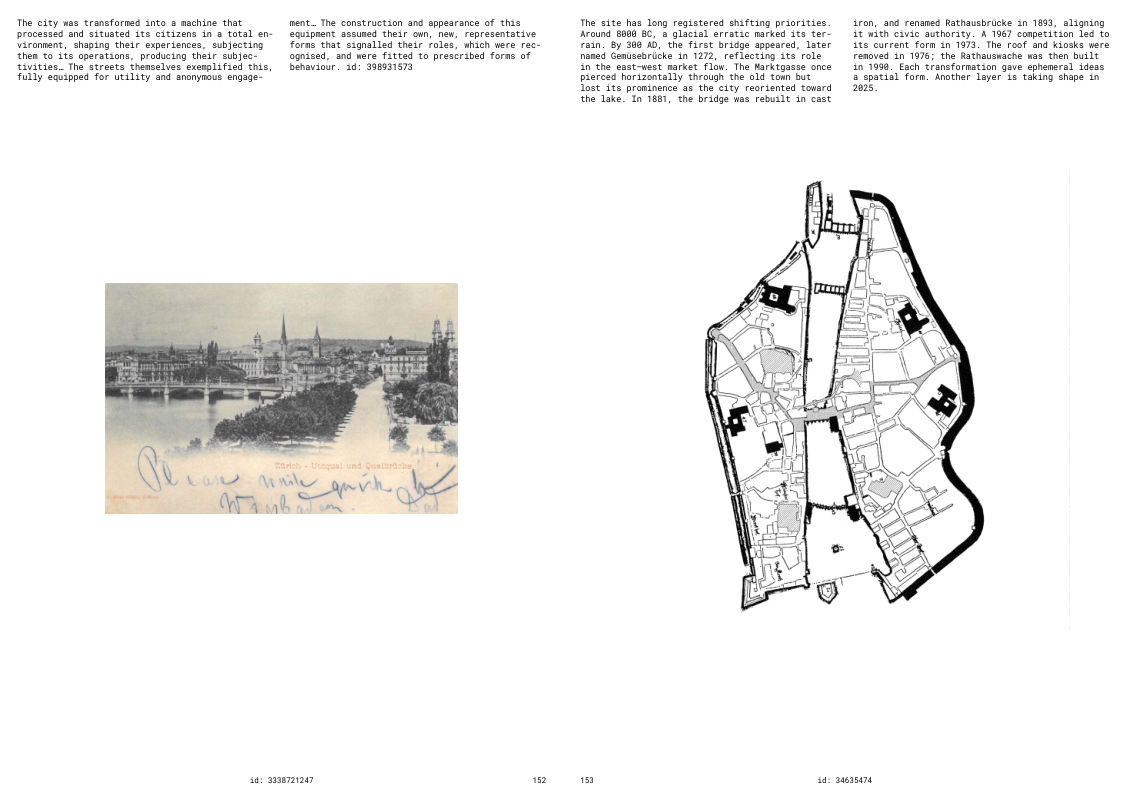

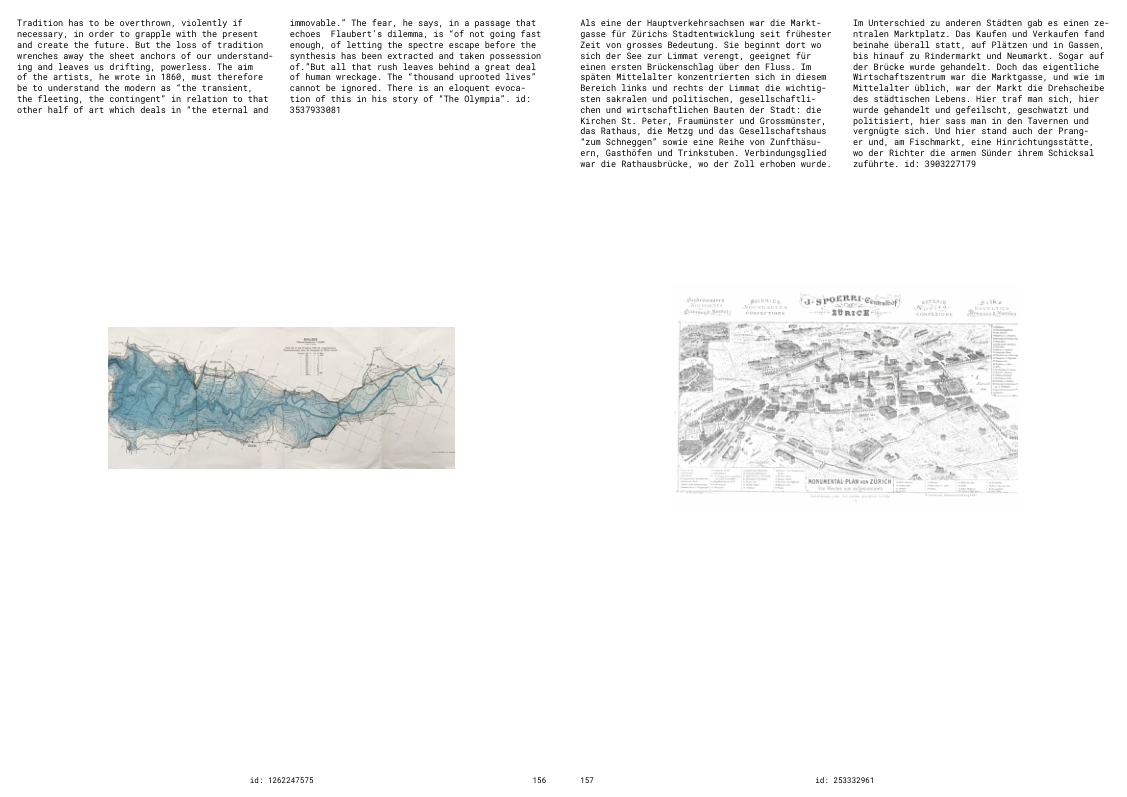

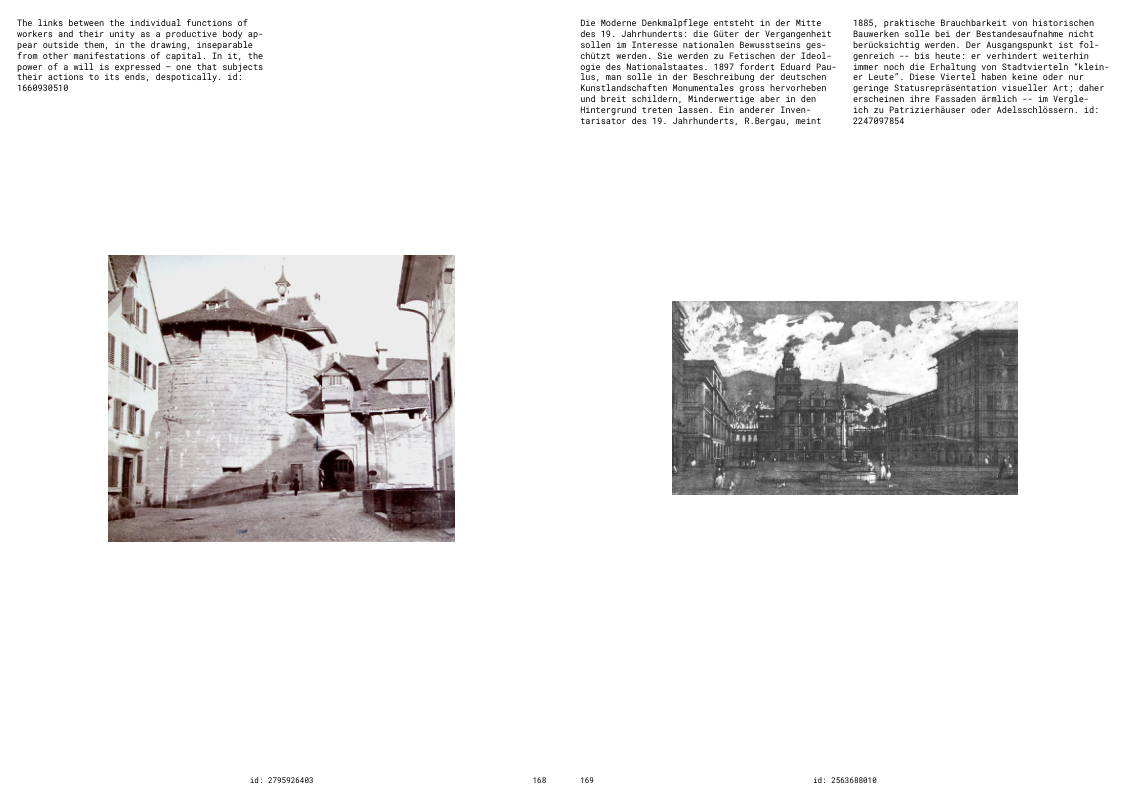

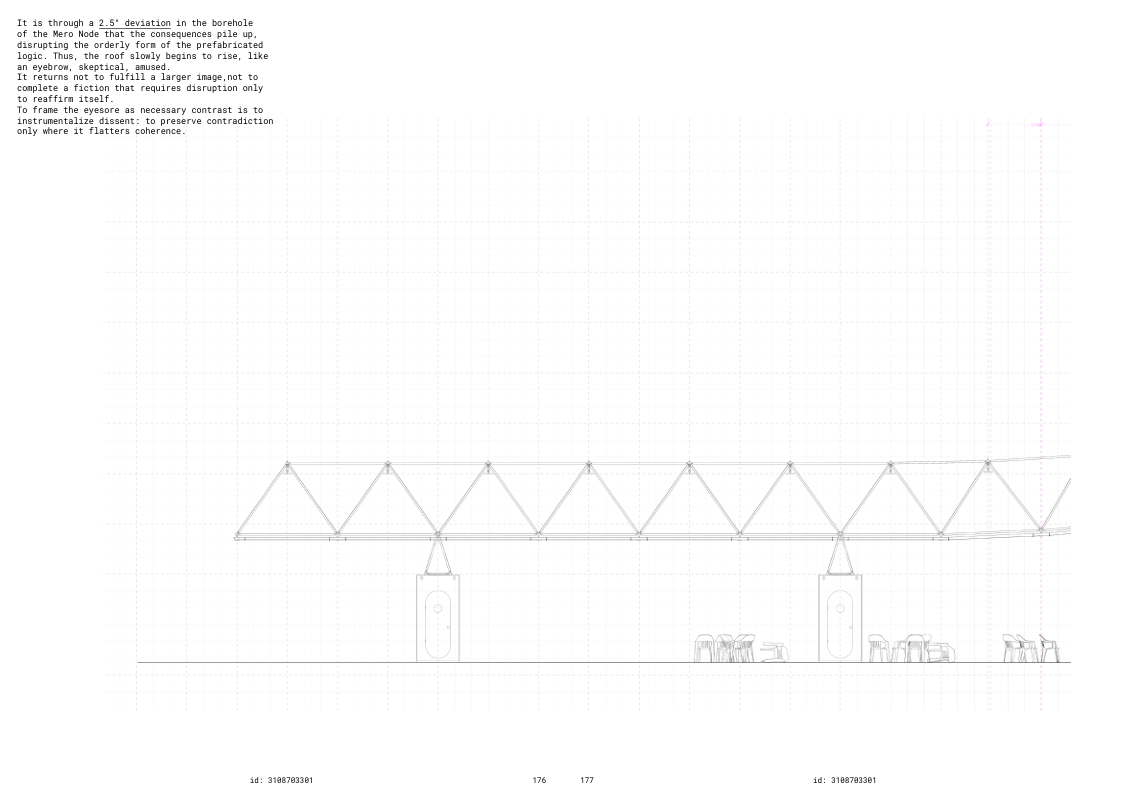

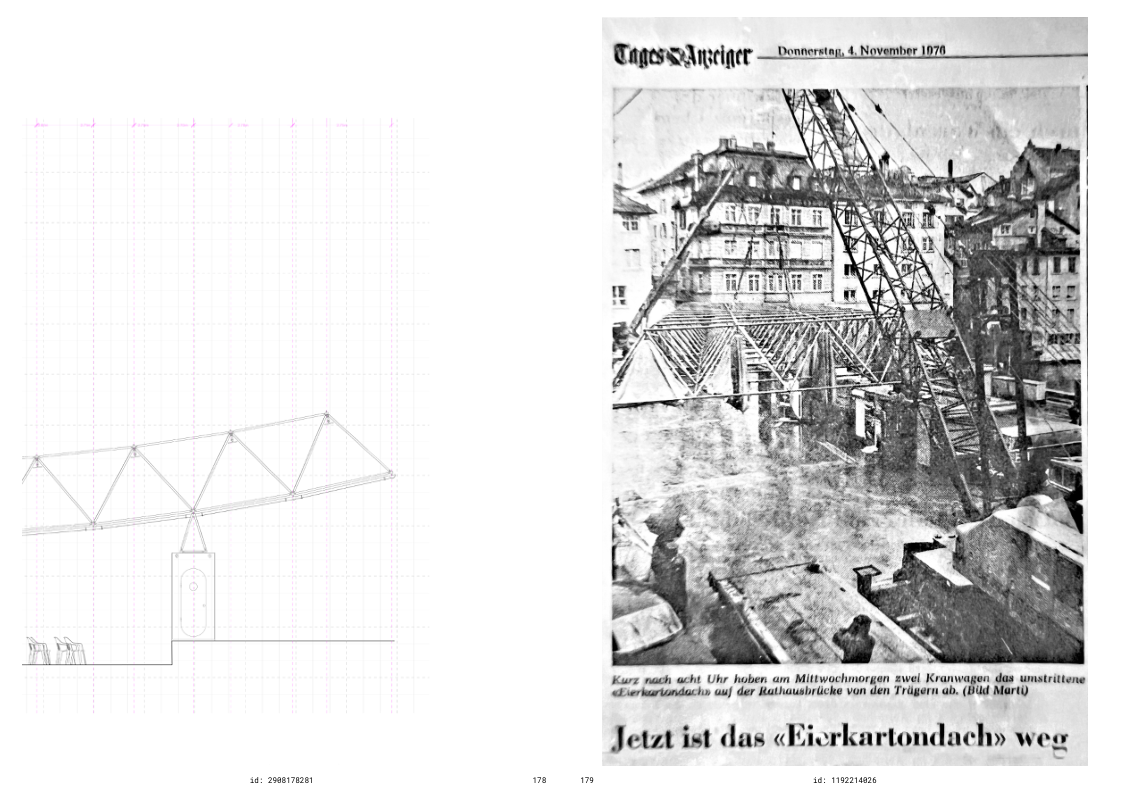

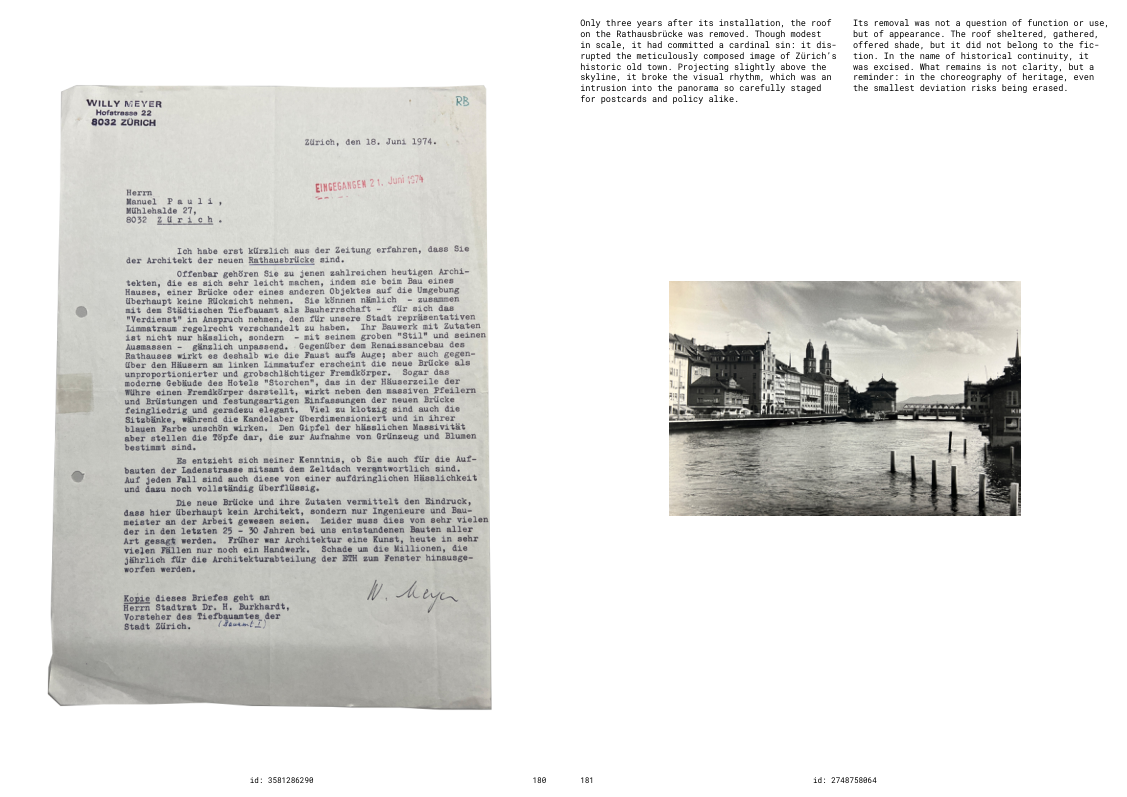

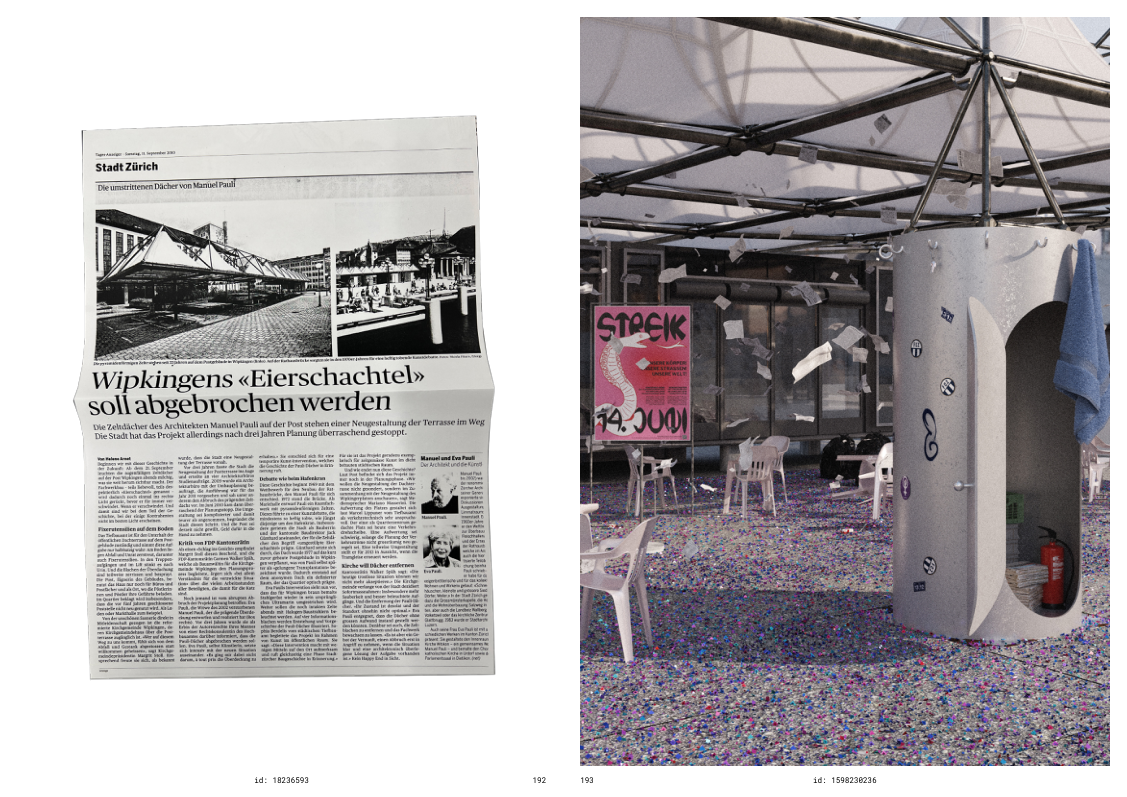

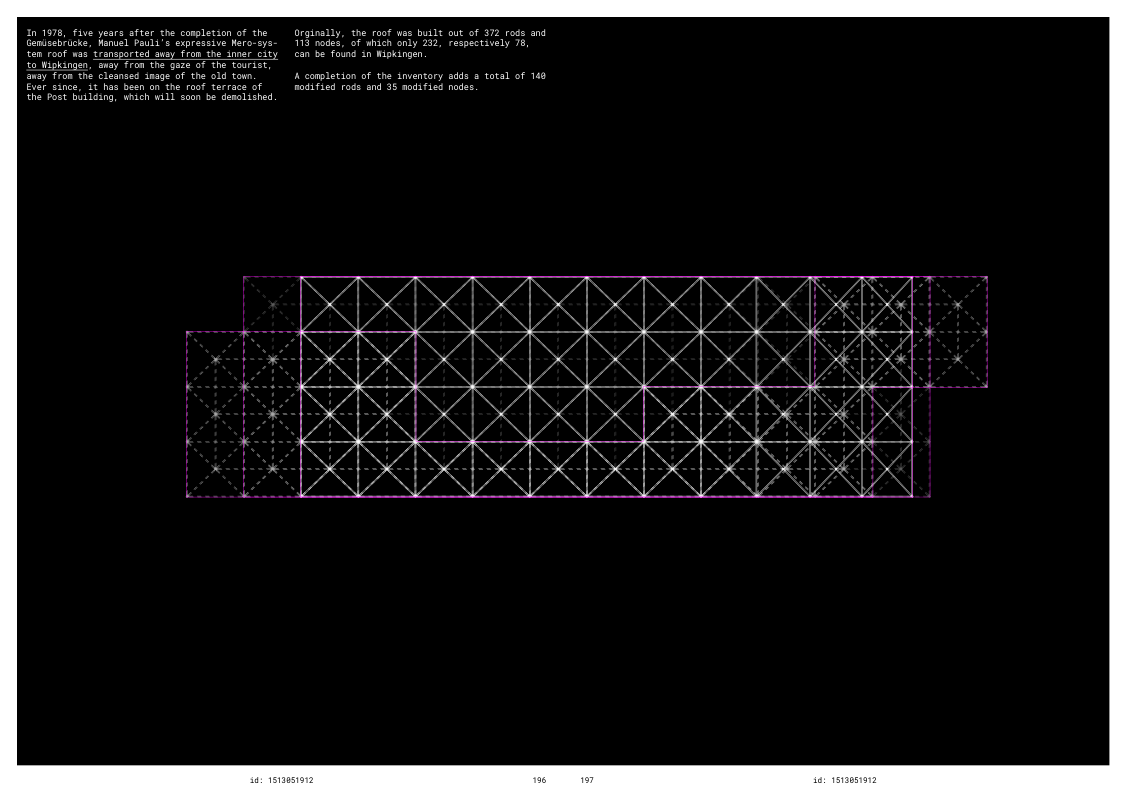

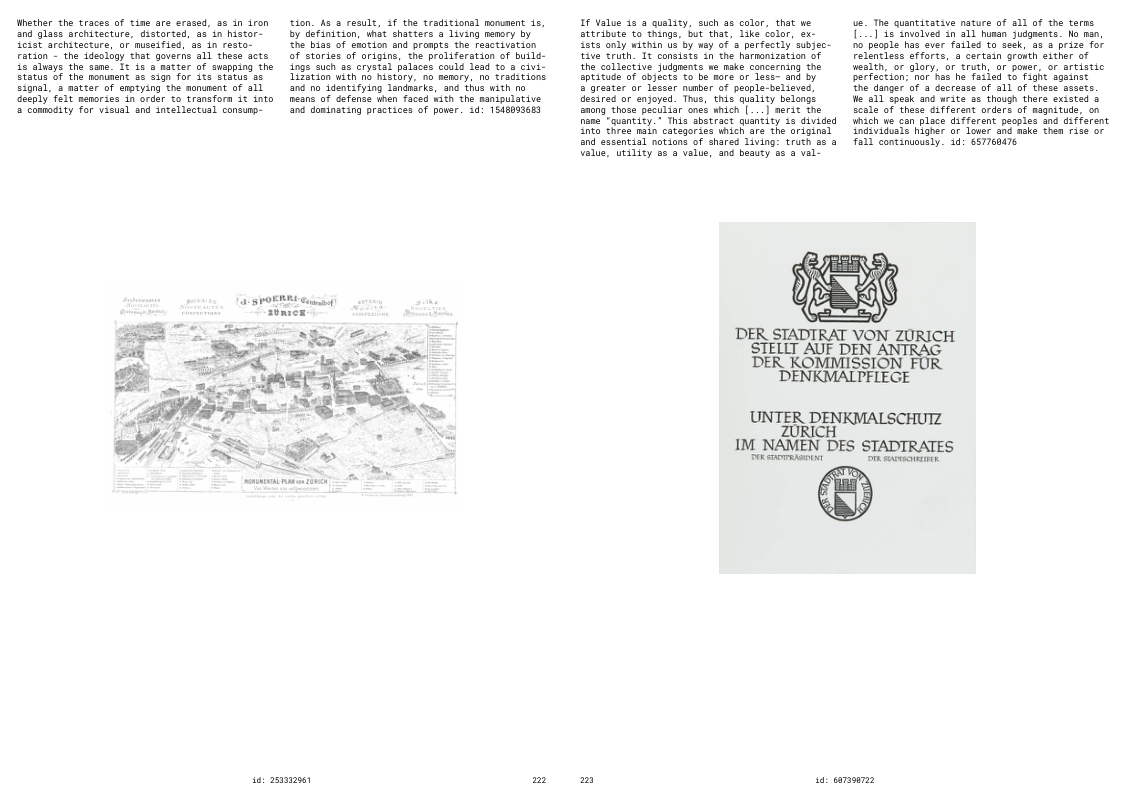

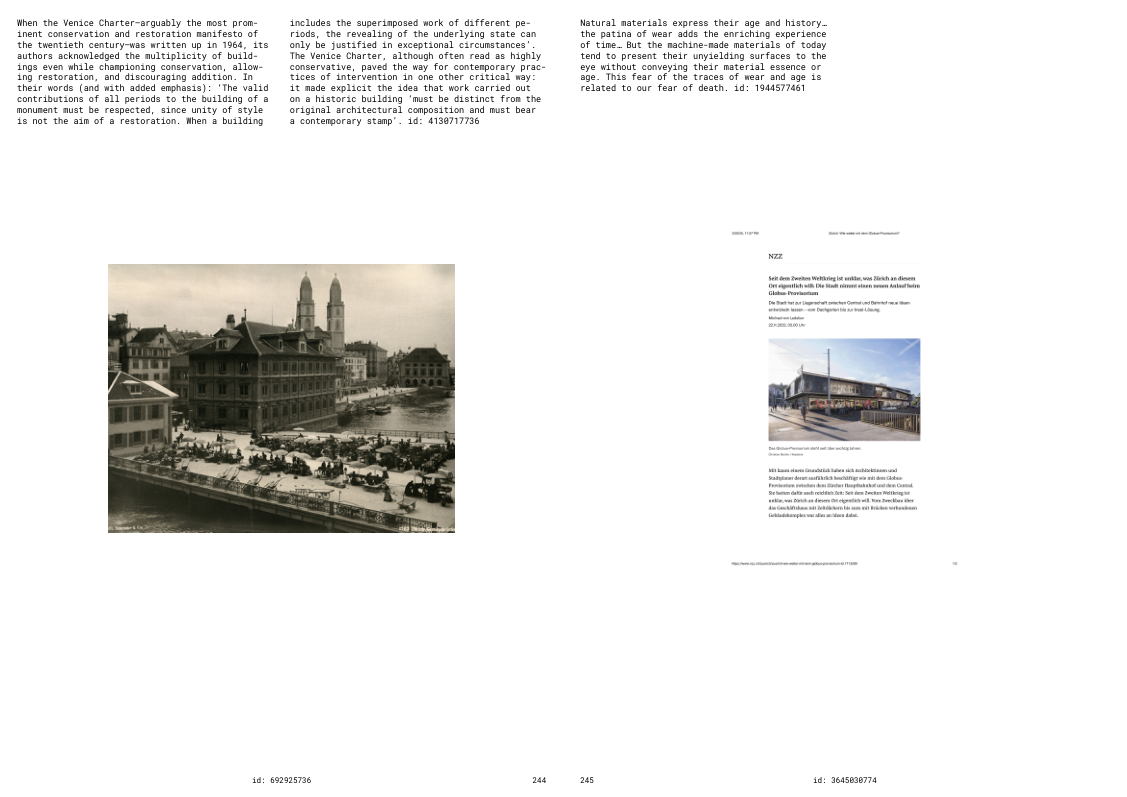

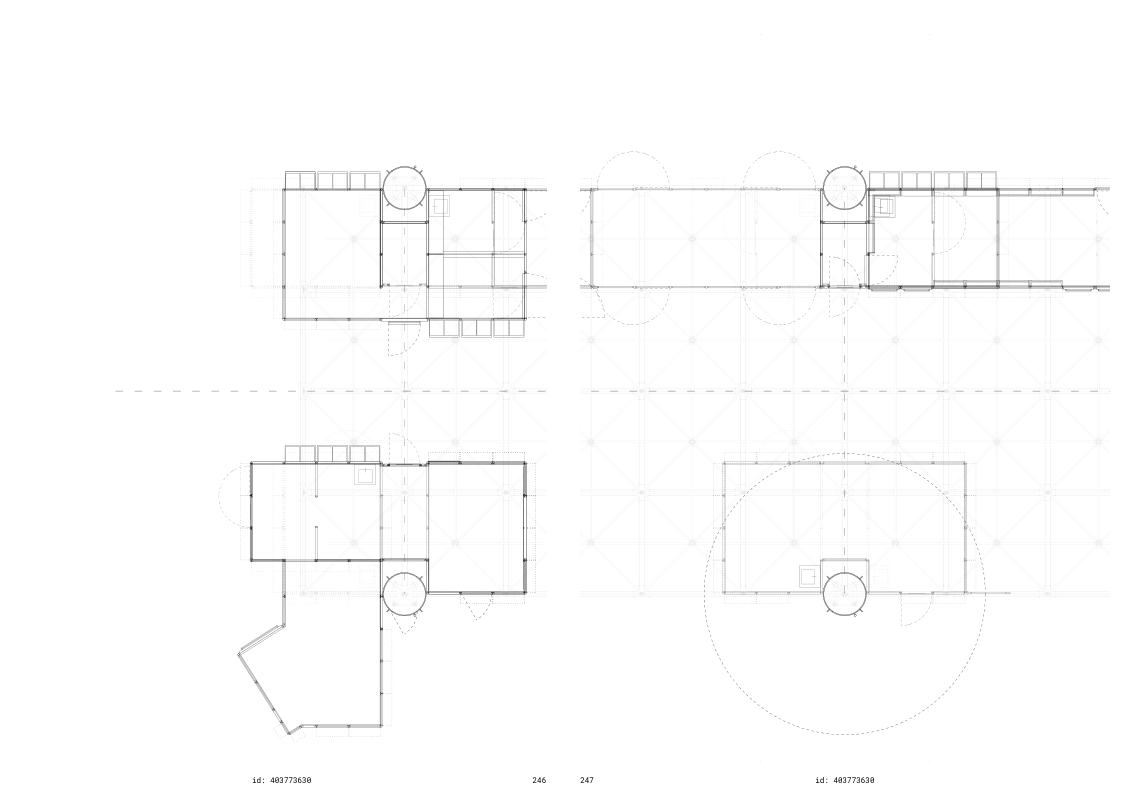

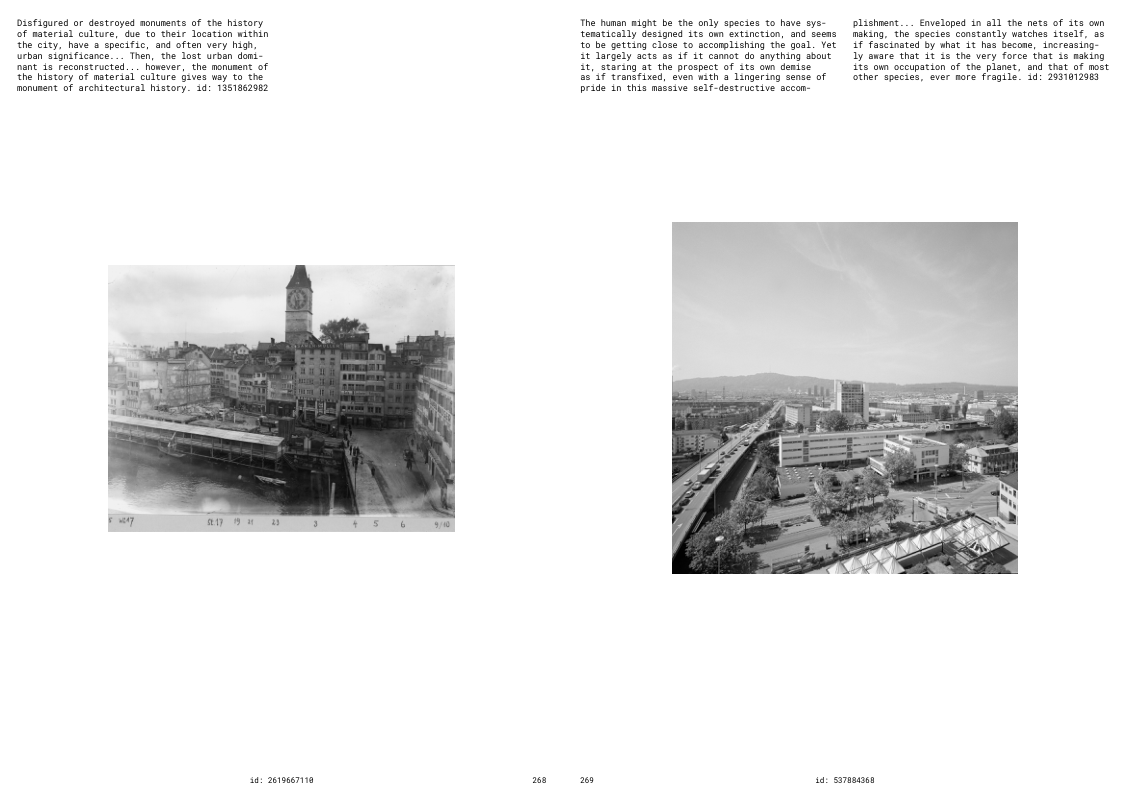

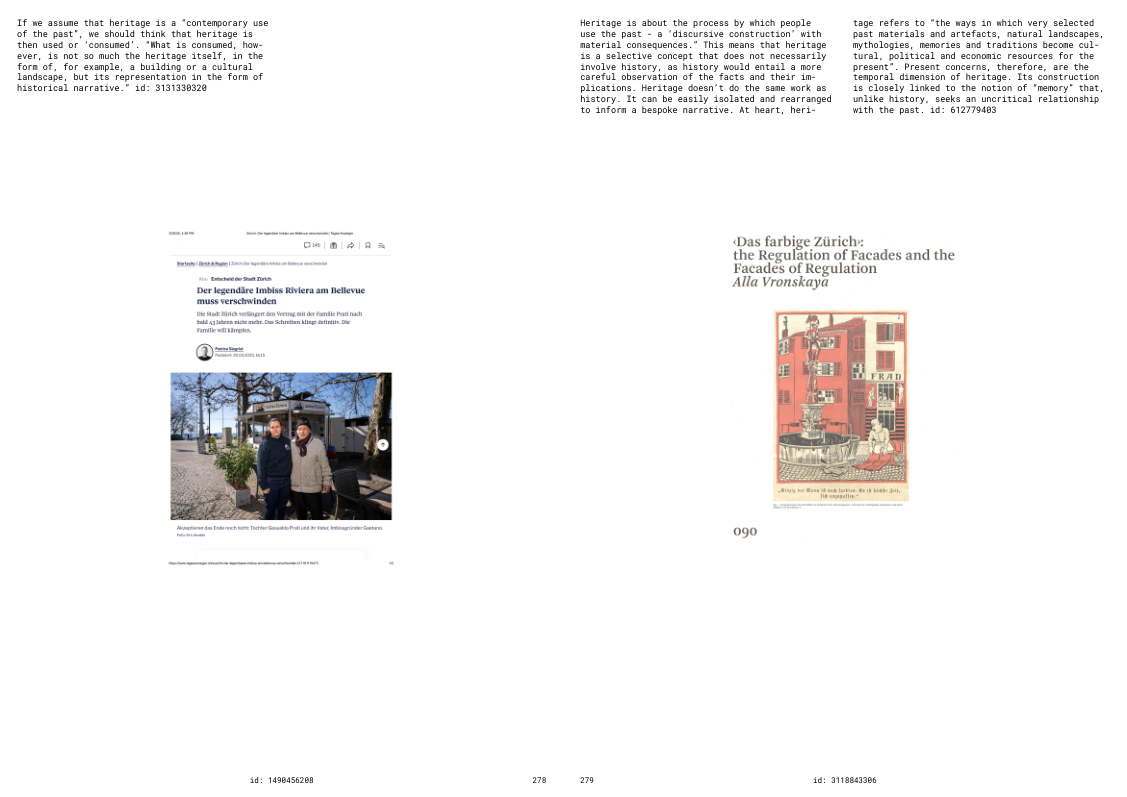

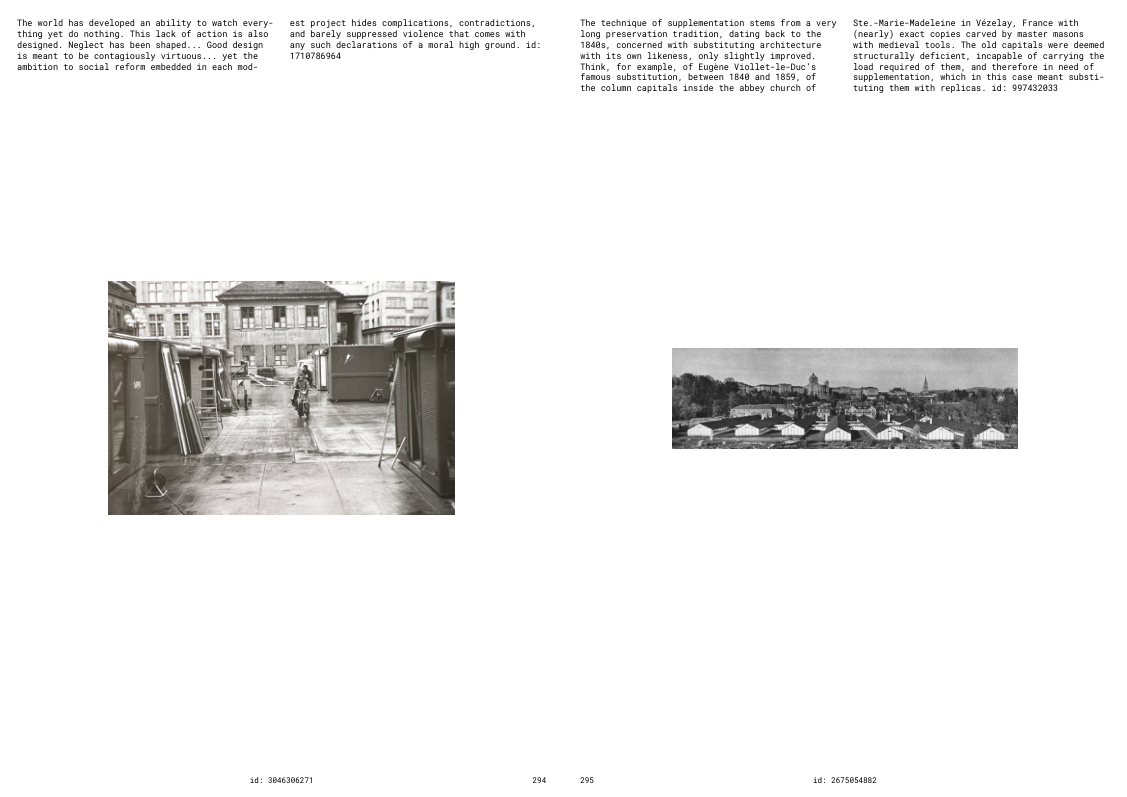

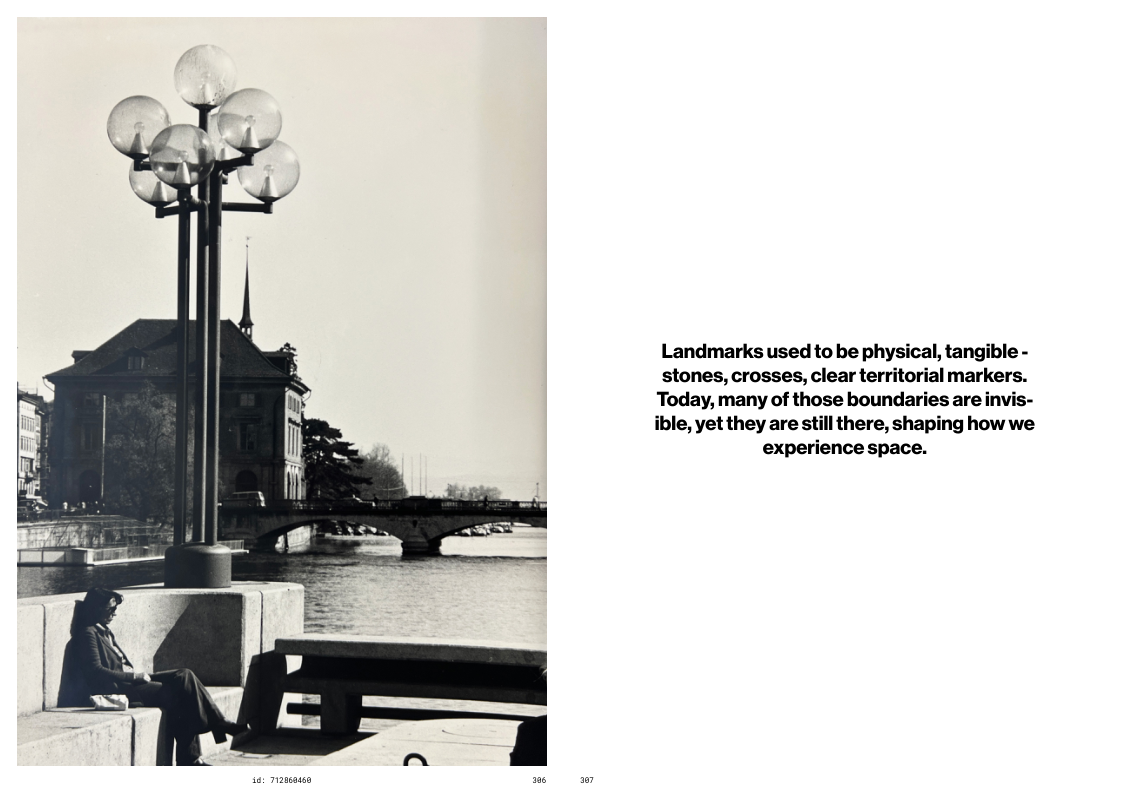

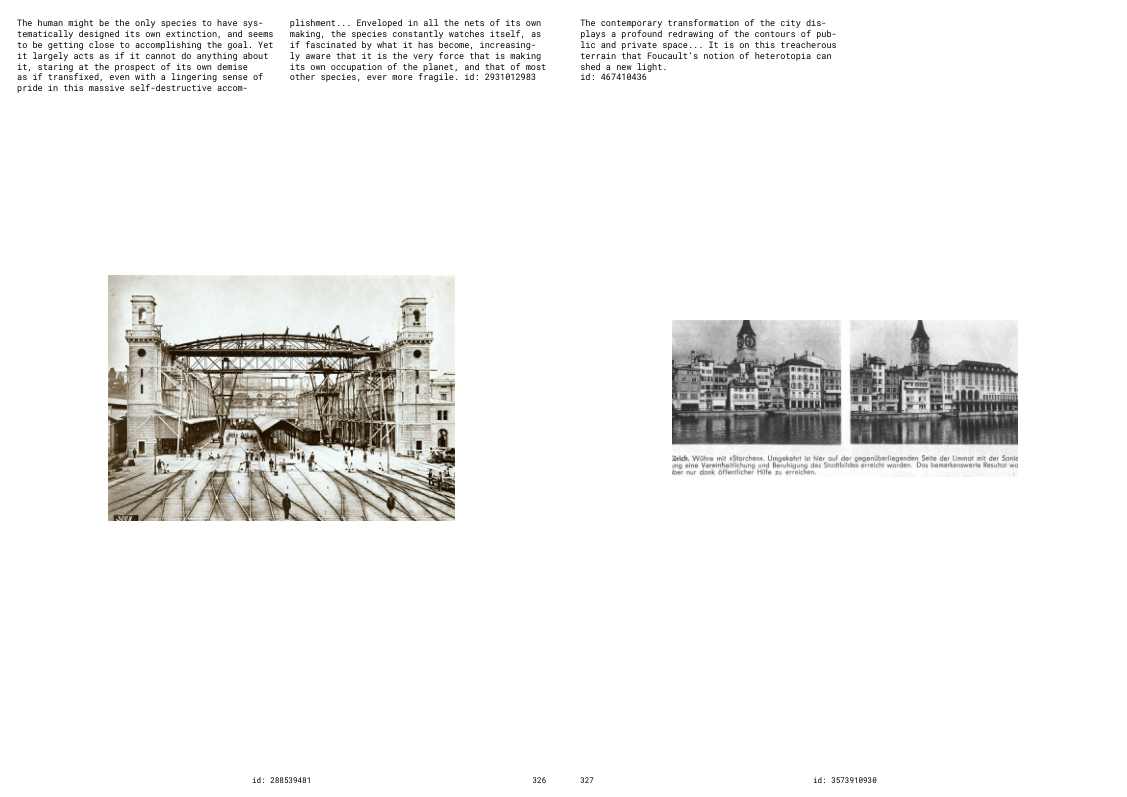

On November 24th, the electorate approved the demolition of the Gemüsebrücke in Zurich, a bridge long regarded as a central urban passage and informal gathering place. The justification for its removal lies in a new hydrological scenario: during extreme rainfall events, particularly those occurring roughly once every 300 years, the Sihl River threatens to overwhelm Zurich’s inner-city flatlands. A relief tunnel, the Entlastungsstollen Thalwil, has been constructed to divert this excess water into Lake Zurich. While this tunnel effectively reduces pressure on the Sihl, it leads to a significant secondary consequence: Lake Zurich’s water level rises by approximately five centimeters, increasing outflow into the Limmat and placing critical stress on downstream infrastructure. The Gemüsebrücke, long subject to aesthetic criticism and disciplinary redesigns since its construction, becomes a hydraulic bottleneck in this chain. As such, its demolition is now framed as a necessary intervention in the city’s updated flood risk management strategy.

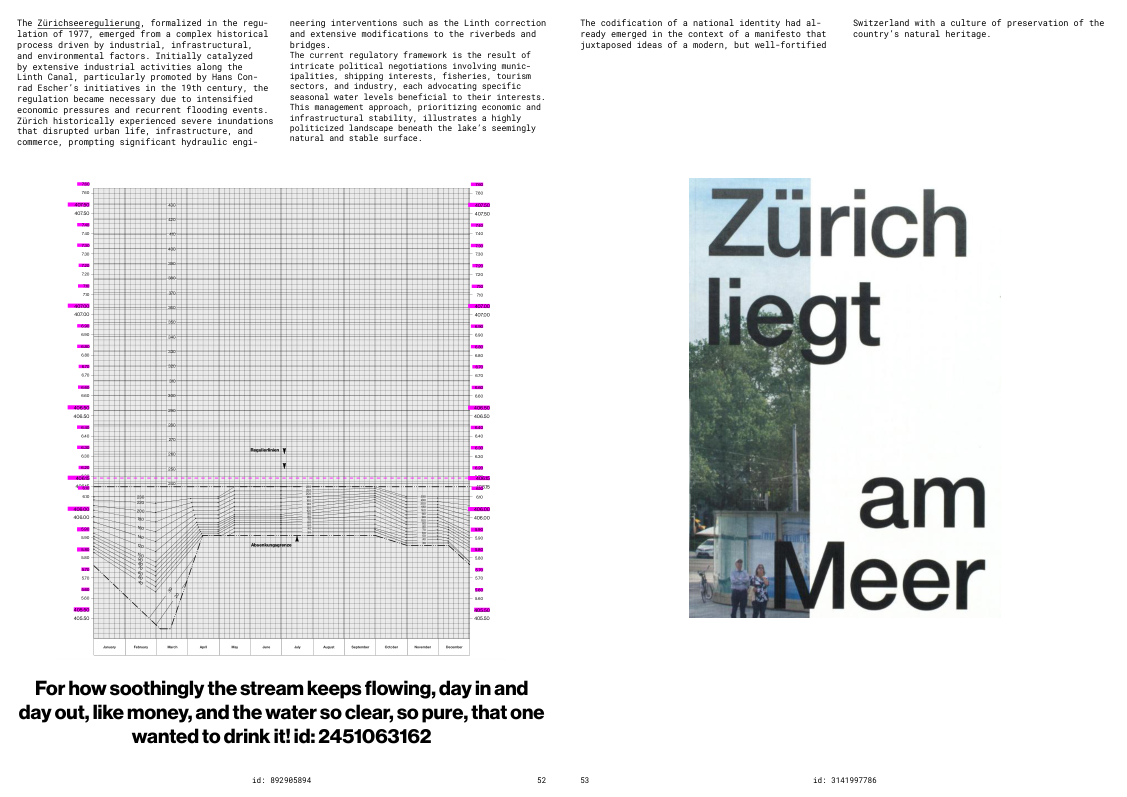

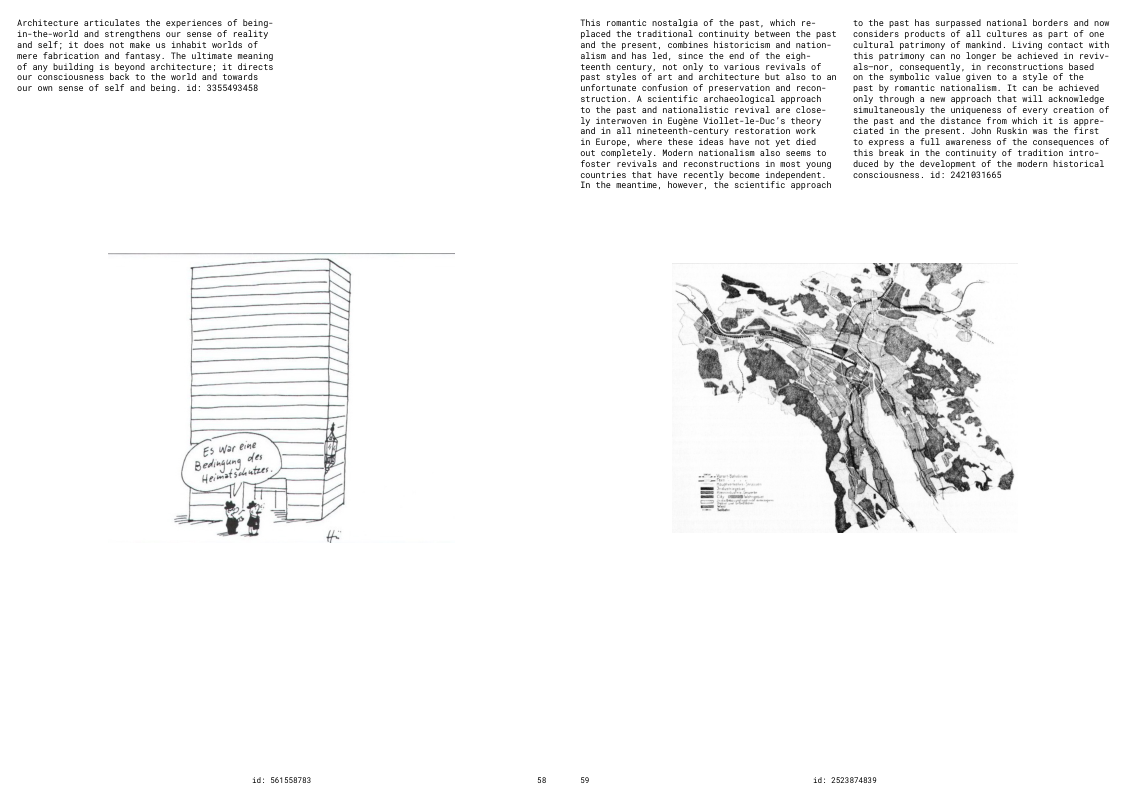

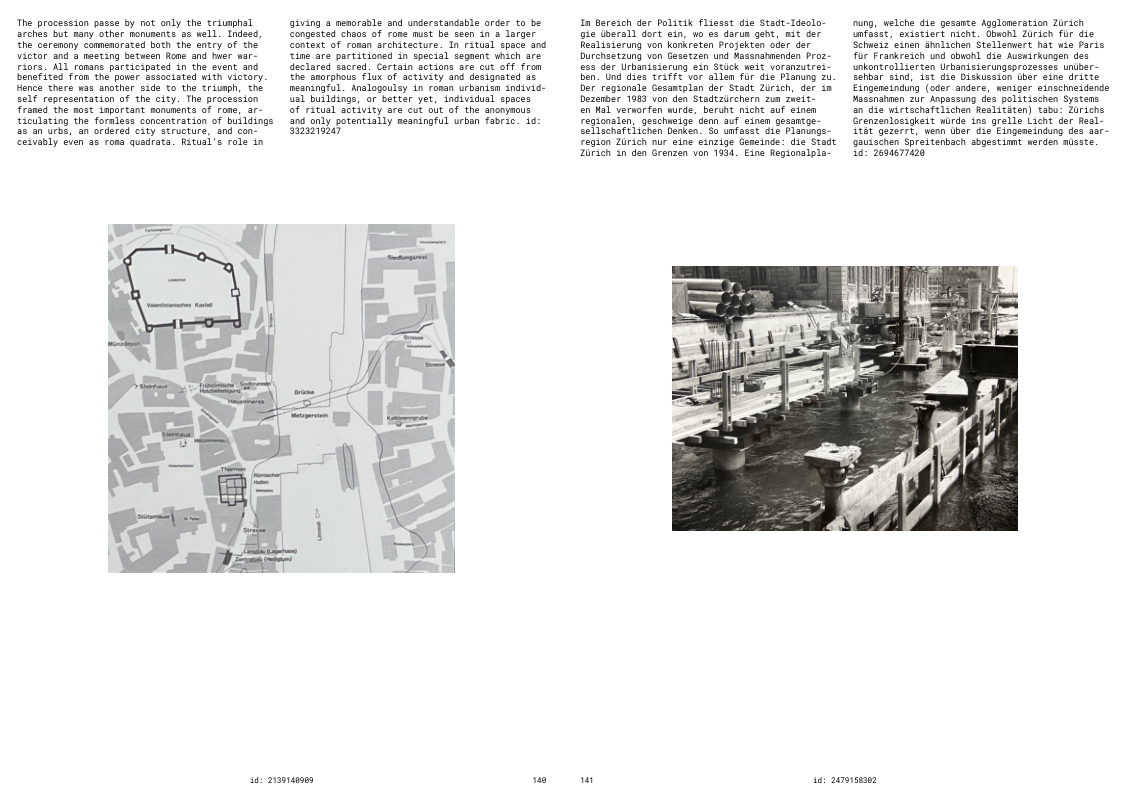

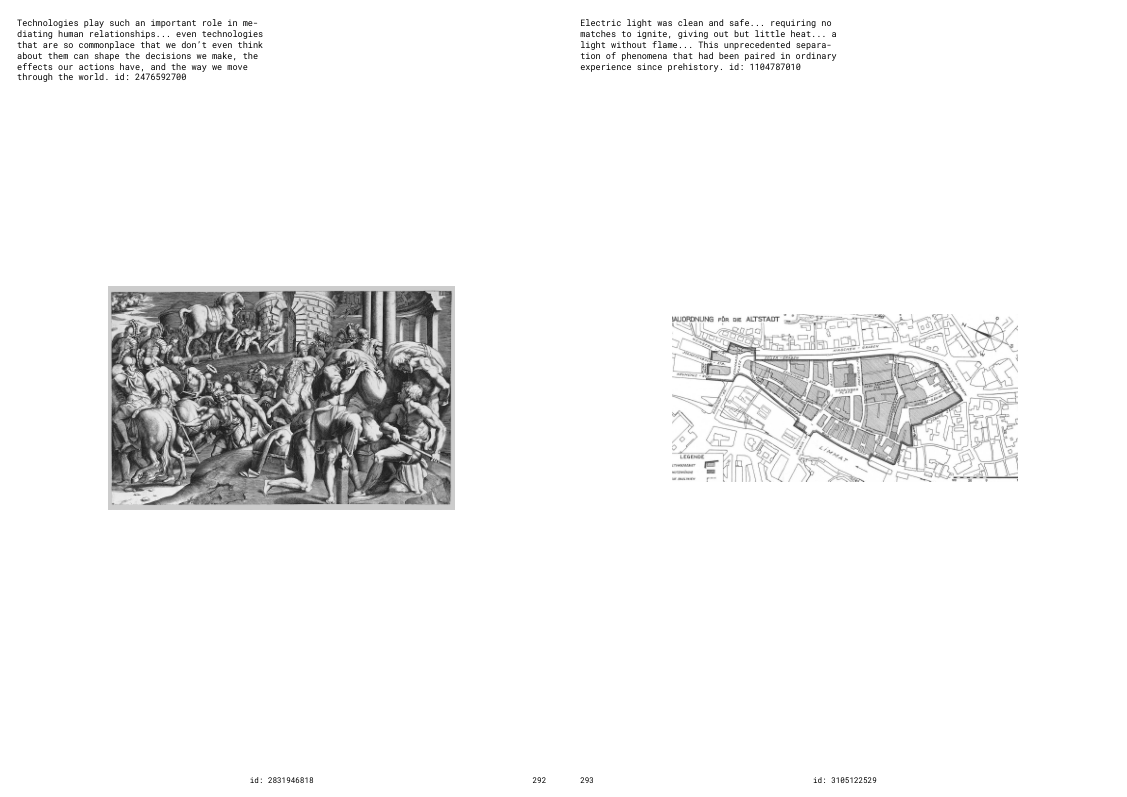

Yet this logic of removal obscures the deeper regulatory infrastructure shaping the situation. The Rathausbrücke’s status as an “obstruction” is not only the result of physical constraints, but also of legal and institutional decisions that govern the behavior of water across Zurich’s territory. Chief among these is the Zürichseeregulierung, the Lake Zurich Regulation Act of 1977. This document, built upon decades of negotiation, dictates the lake’s monthly water levels and outlines official measures for flood events. Crucially, it is not the Limmat’s physical capacity that determines outflow volumes from the lake, but a politically constructed legal framework.

COSMOSCOPE

COSMOSCOPE

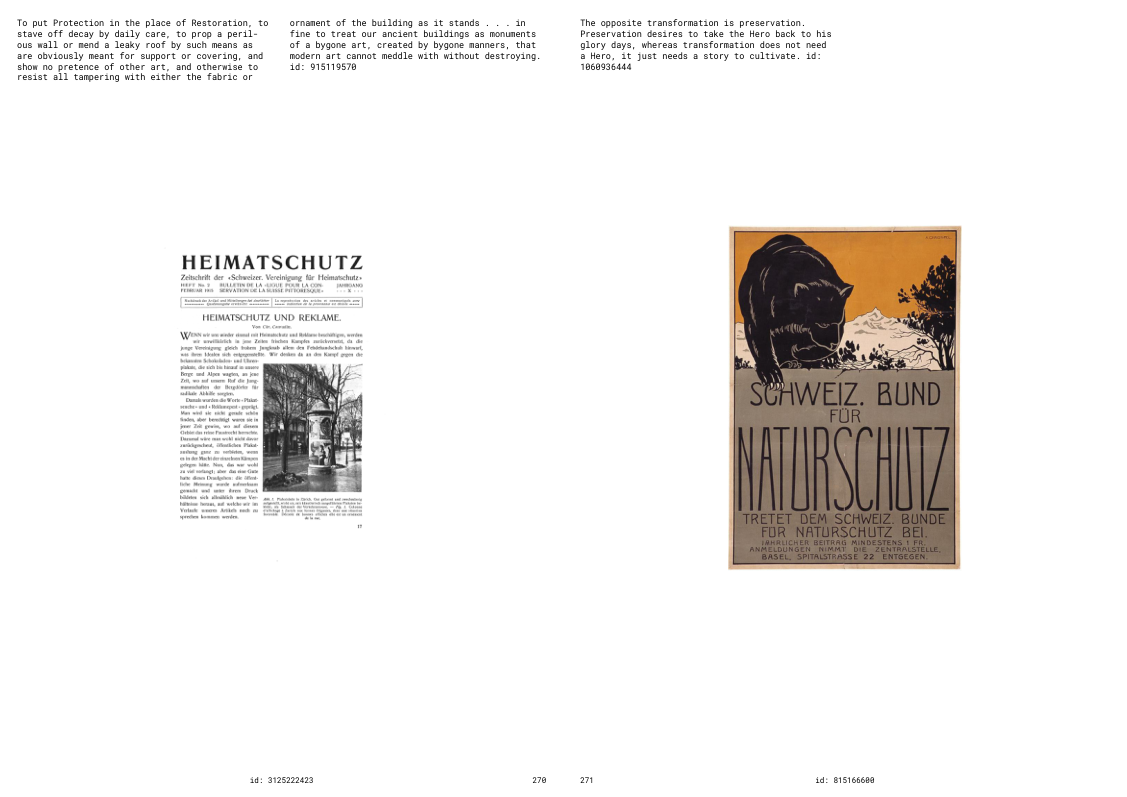

The regulation operates with a seasonal curve: water levels are adjusted monthly according to agreements between stakeholders including lakeside municipalities, the navigation authority, energy companies, tourism, and fisheries. The Limmat’s role as a navigable waterway is especially influential. Maintaining high lake levels ensures that boats can continue to operate downstream, an economic and symbolic priority that often overrides alternative flood mitigation strategies.

In this context, the relief tunnel’s design, while effective in redistributing floodwaters from the Sihl, places additional stress on the Limmat not by necessity, but by regulation. One feasible solution, the preemptive lowering of Lake Zurich prior to major weather events, is technically simple and legally possible within the existing regulatory framework.

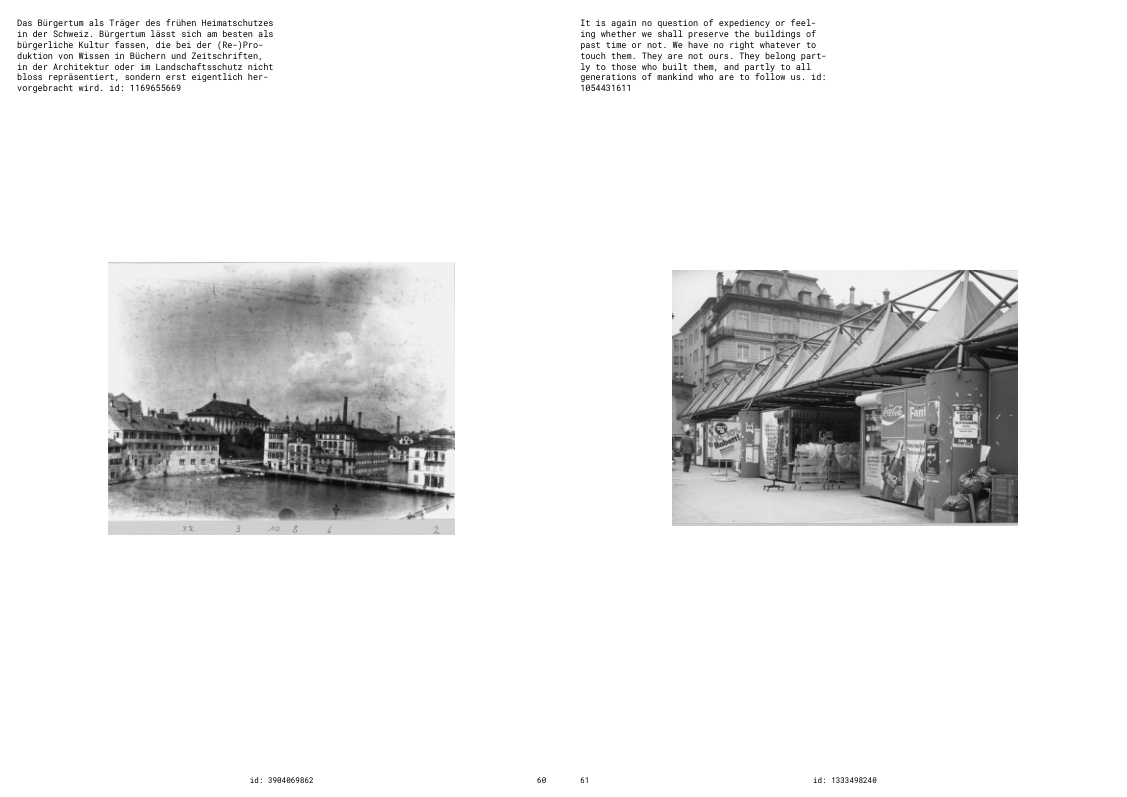

However, such a measure has been repeatedly sidelined, not due to technical infeasibility, but to avoid disrupting navigation on the Limmat. Specifically, the regulation protects the uninterrupted operation of the Limmat passenger boats, a hallmark of Zurich’s touristic self-image. The political weight assigned to maintaining this navigation, ensuring that the boats can continue their smooth passage along the river, has consistently outweighed considerations for infrastructural alternatives such as the preemptive lowering of Lake Zurich.

It is important to note that such a preemptive adjustment would only marginally interfere with navigation, and only in the narrow temporal window preceding an extreme flood event. Yet this brief potential disruption has proven politically more sensitive than the structural fate of the Rathausbrücke itself. In this light, the bridge is not demolished solely for reasons of safety or flow efficiency, but because it is less symbolically protected than the daily, effortless glide of the tourist boats, vessels whose smooth passage has come to embody the city’s image of stability, purity, control and opportunism.

COSMOSCOPE

COSMOSCOPE

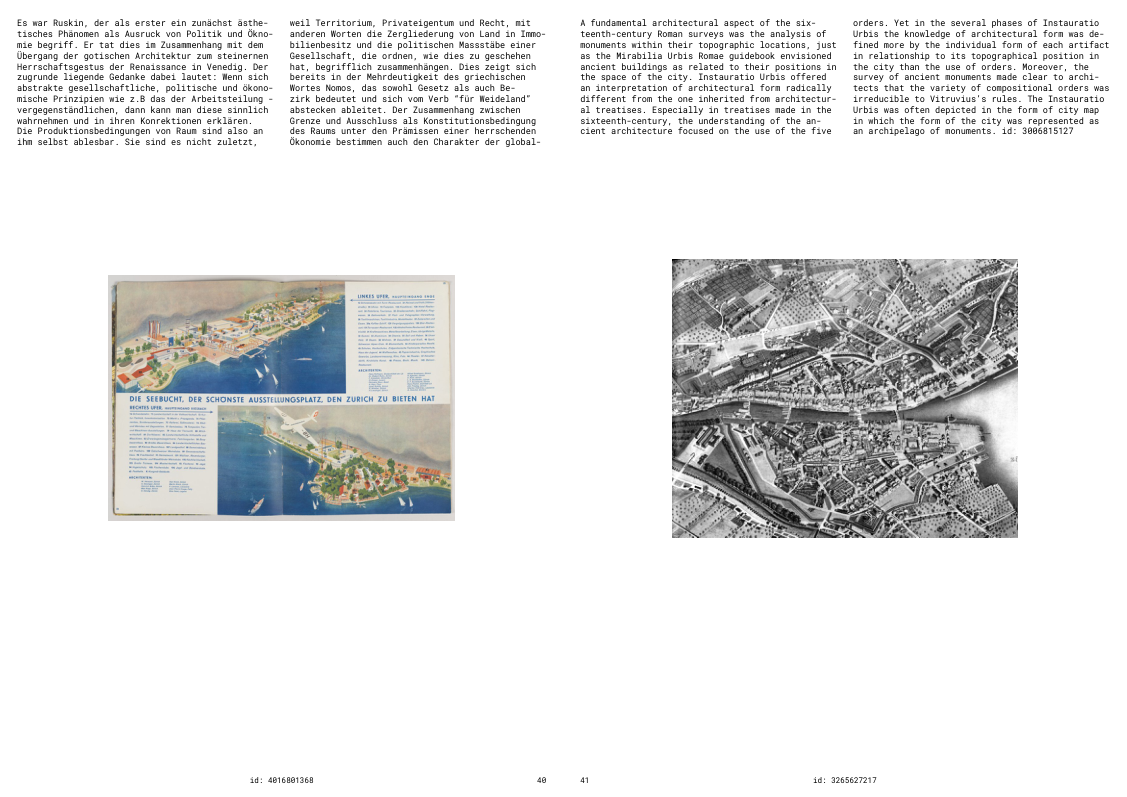

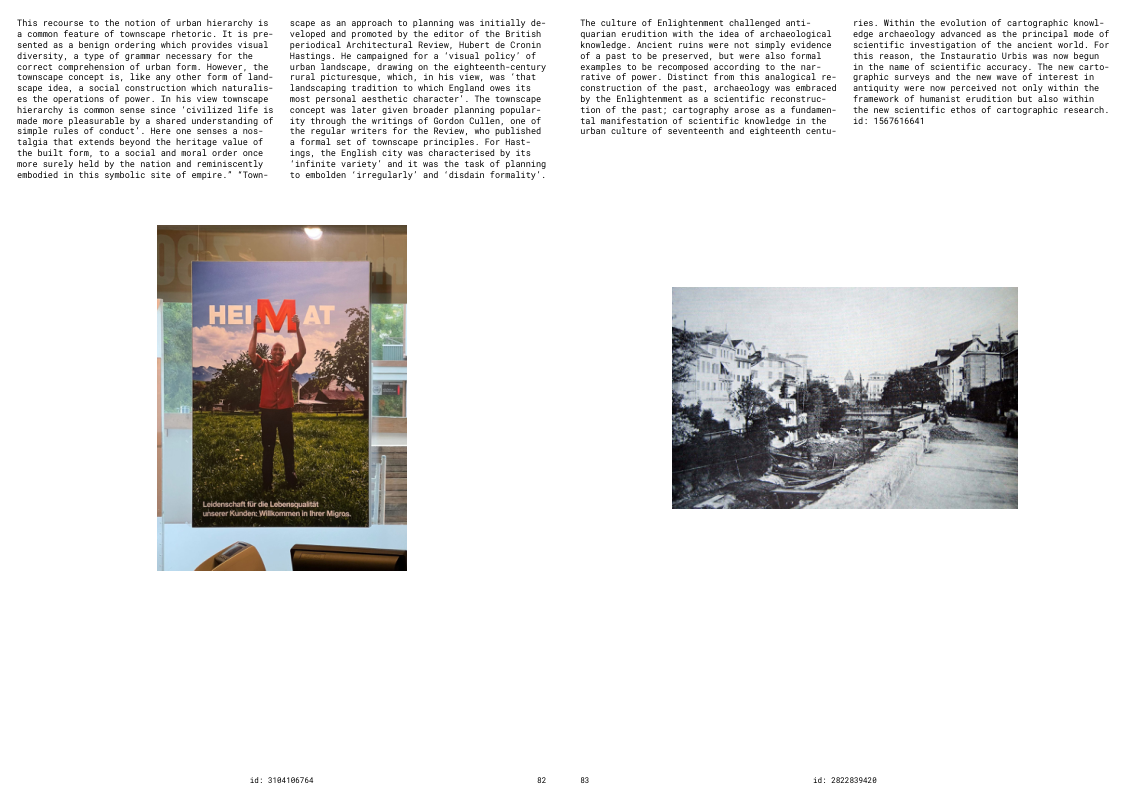

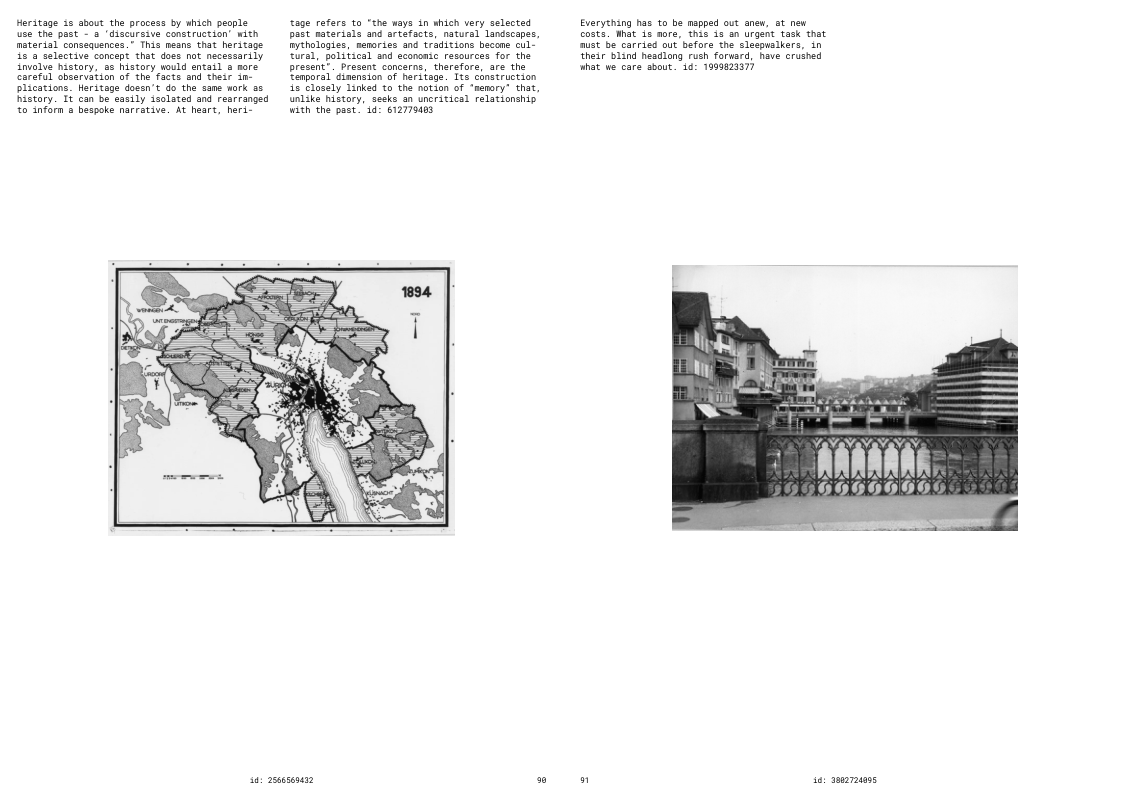

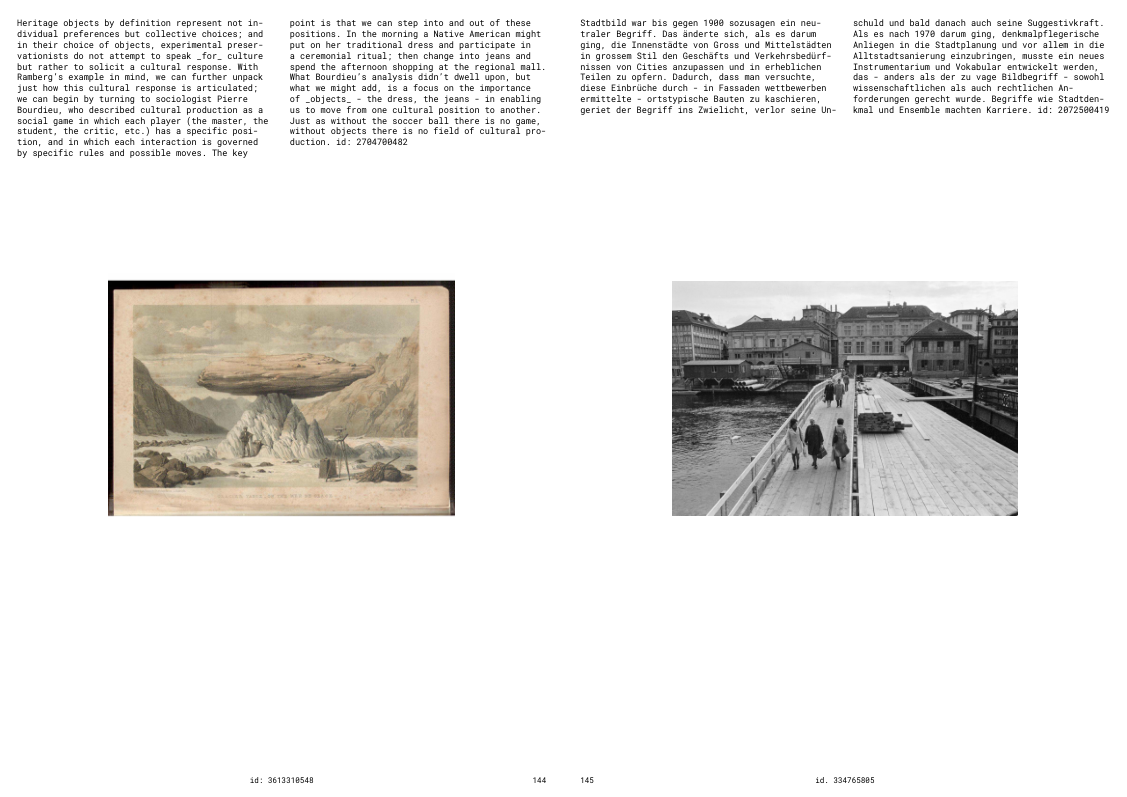

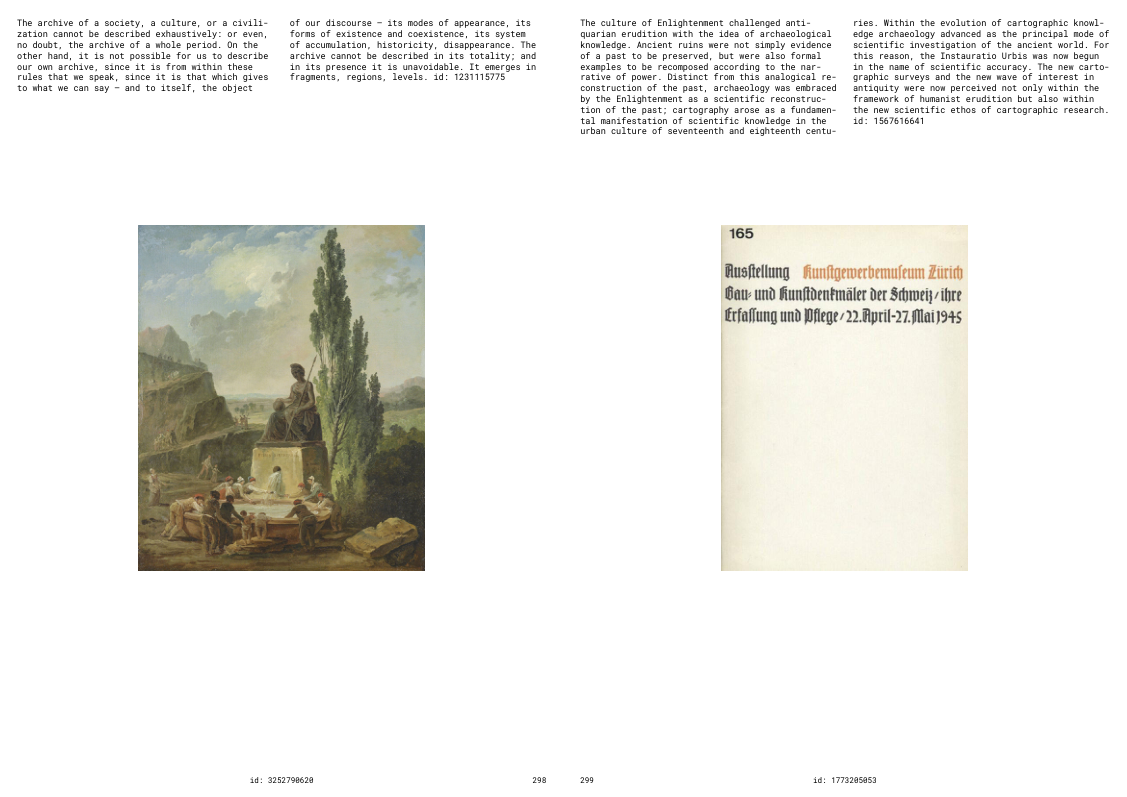

We therefore ask what might happen if the Gemüsebrücke were given a seat at the table, if, through a formal act of protection, it were acknowledged not as an obstruction but as a participant in Zurich’s hydrological and political landscape. What remains unspoken in this regulatory regime is not only a logic of flow, safety, and optimization, but also a deeply embedded notion of belonging, of what is to be preserved, and for whom. The technical language of flood prevention and water regulation, while appearing neutral and procedural, is underwritten by a tacit vision of Heimat: a desire for stability, continuity, and a controlled environment in which daily life, commerce, tourism, navigation, can unfold undisturbed.

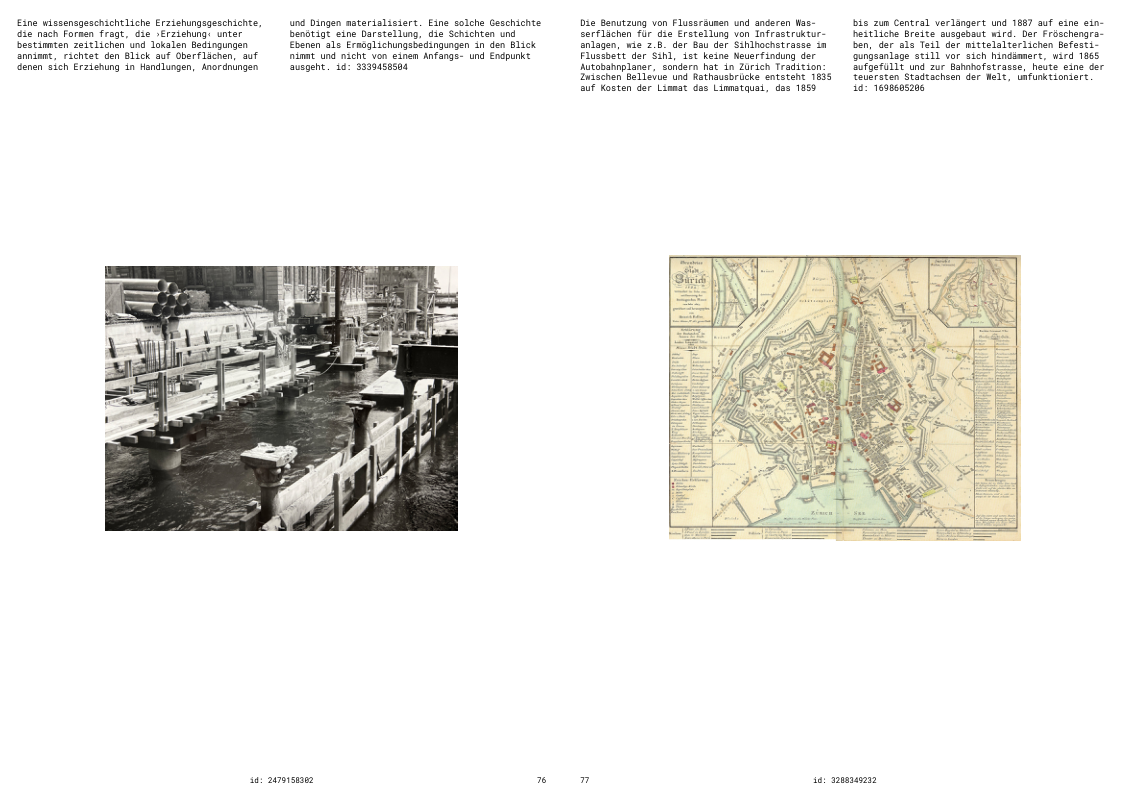

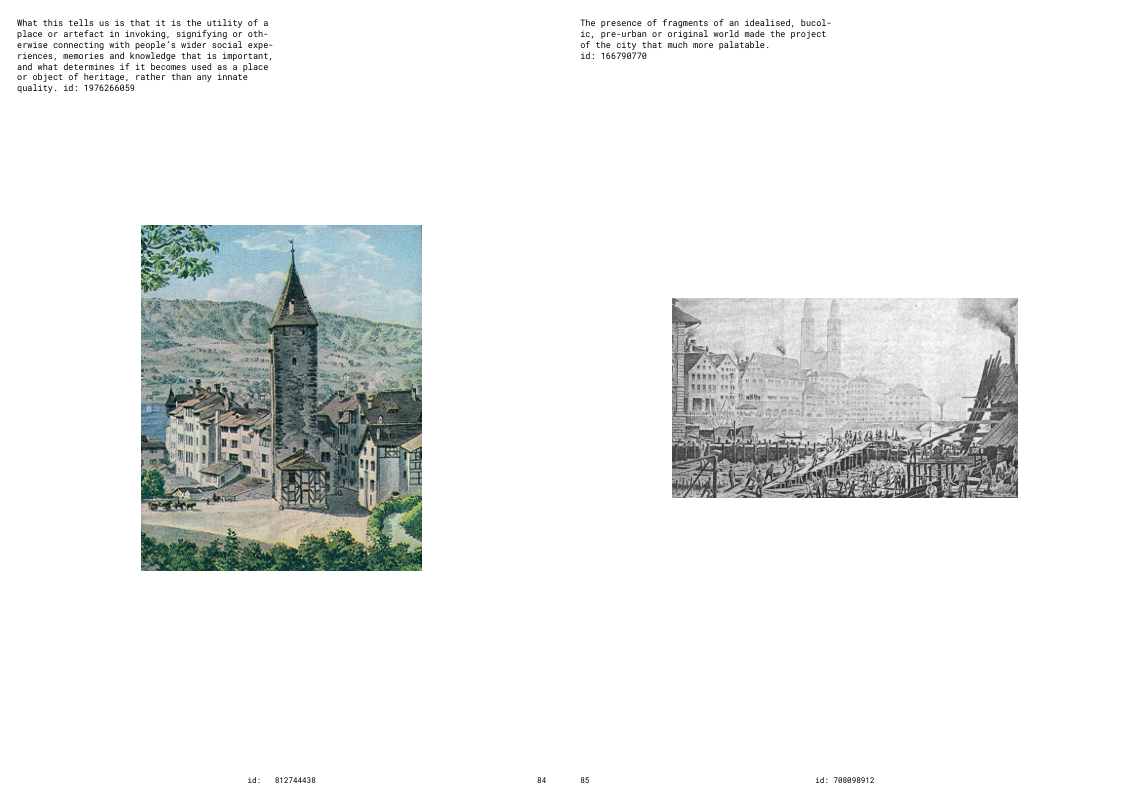

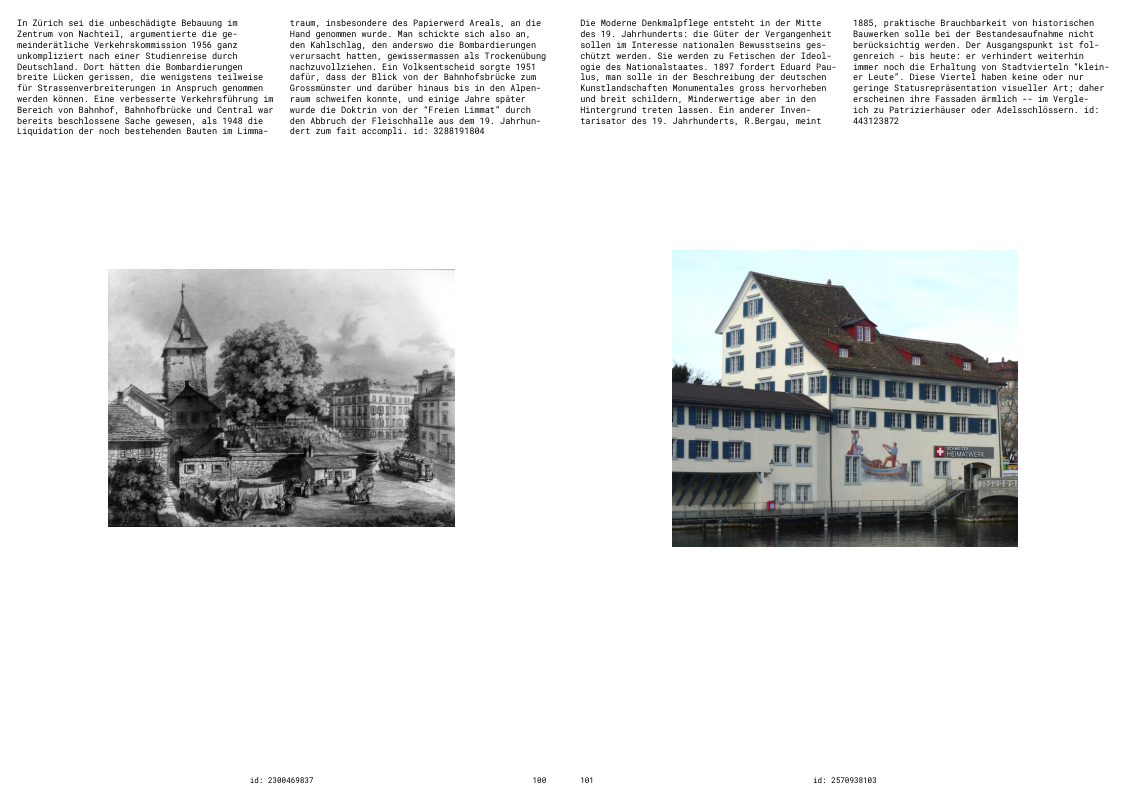

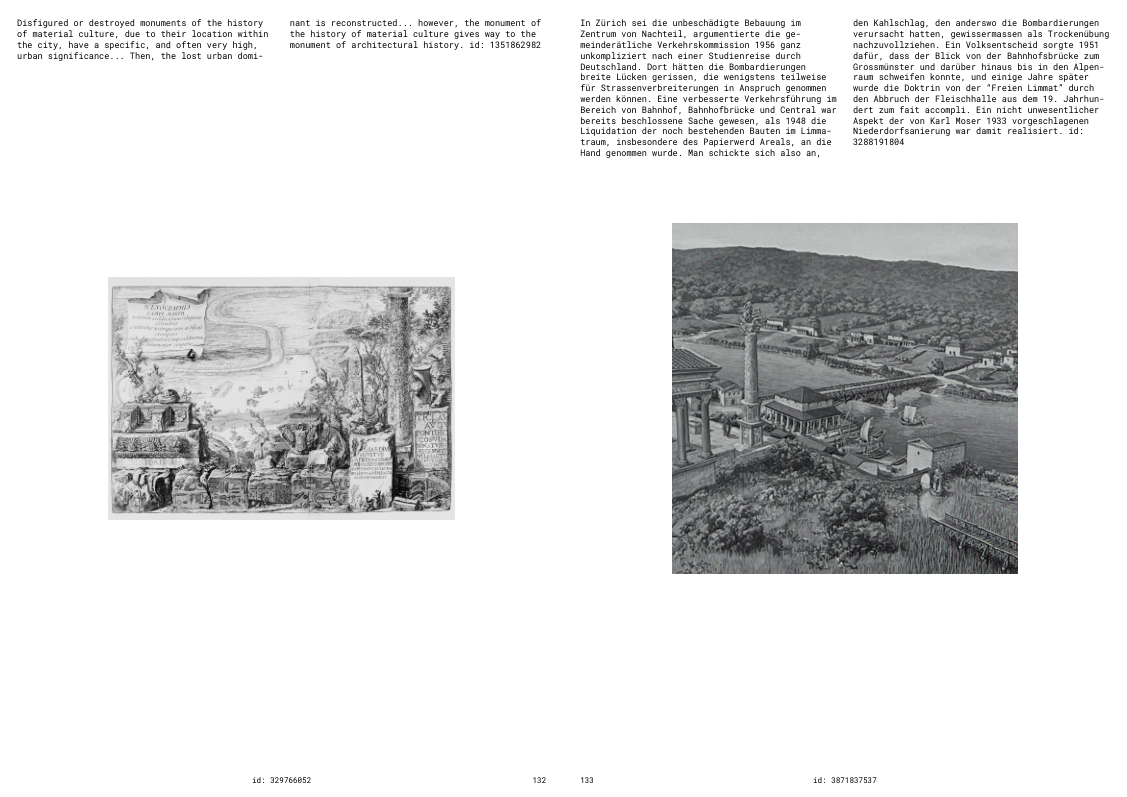

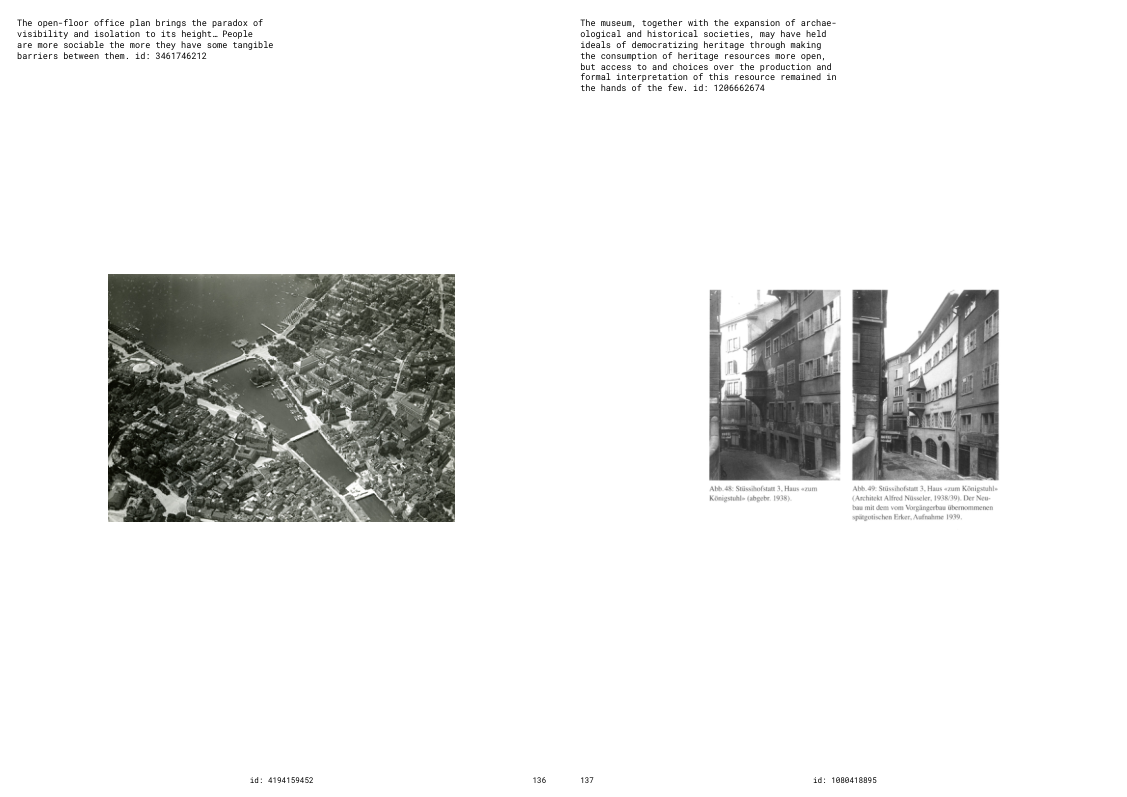

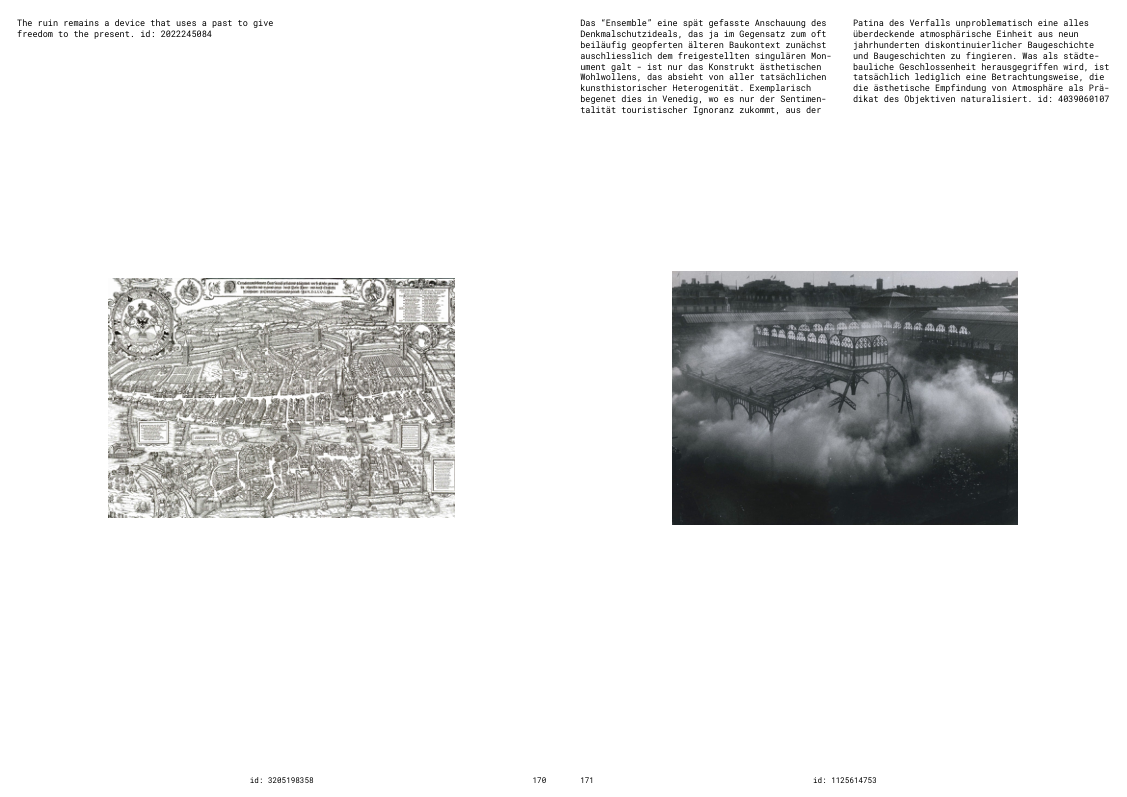

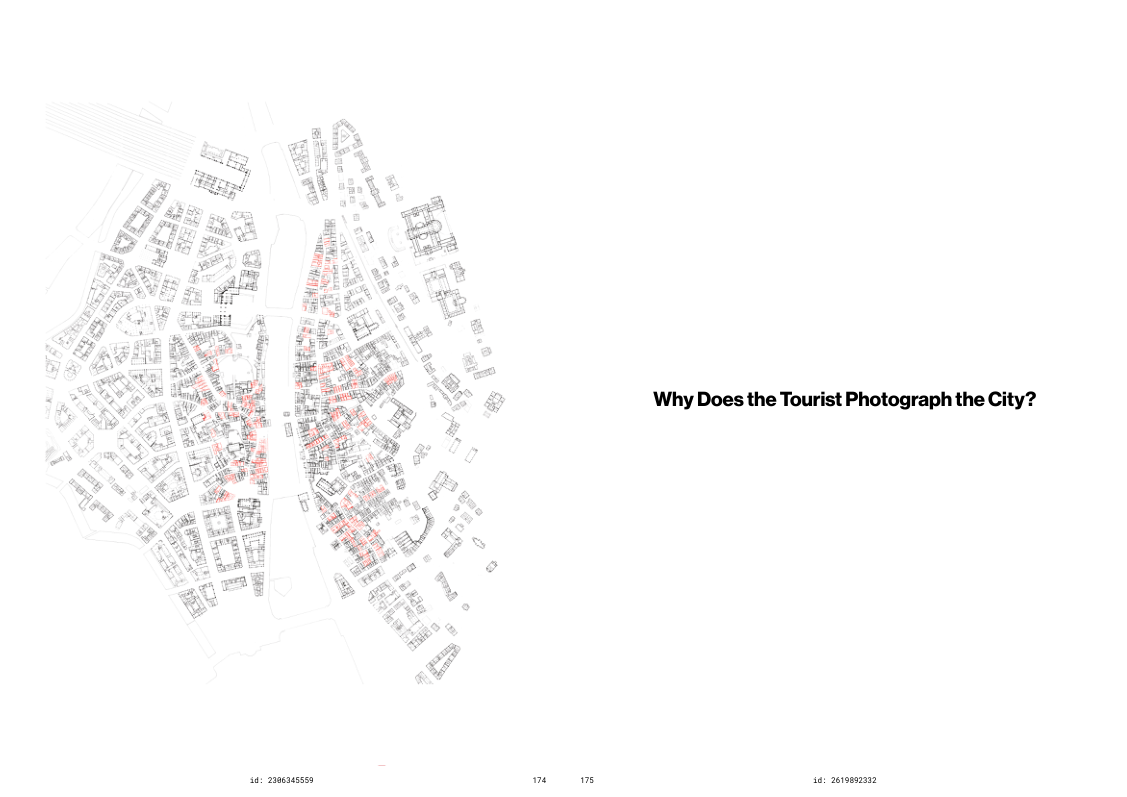

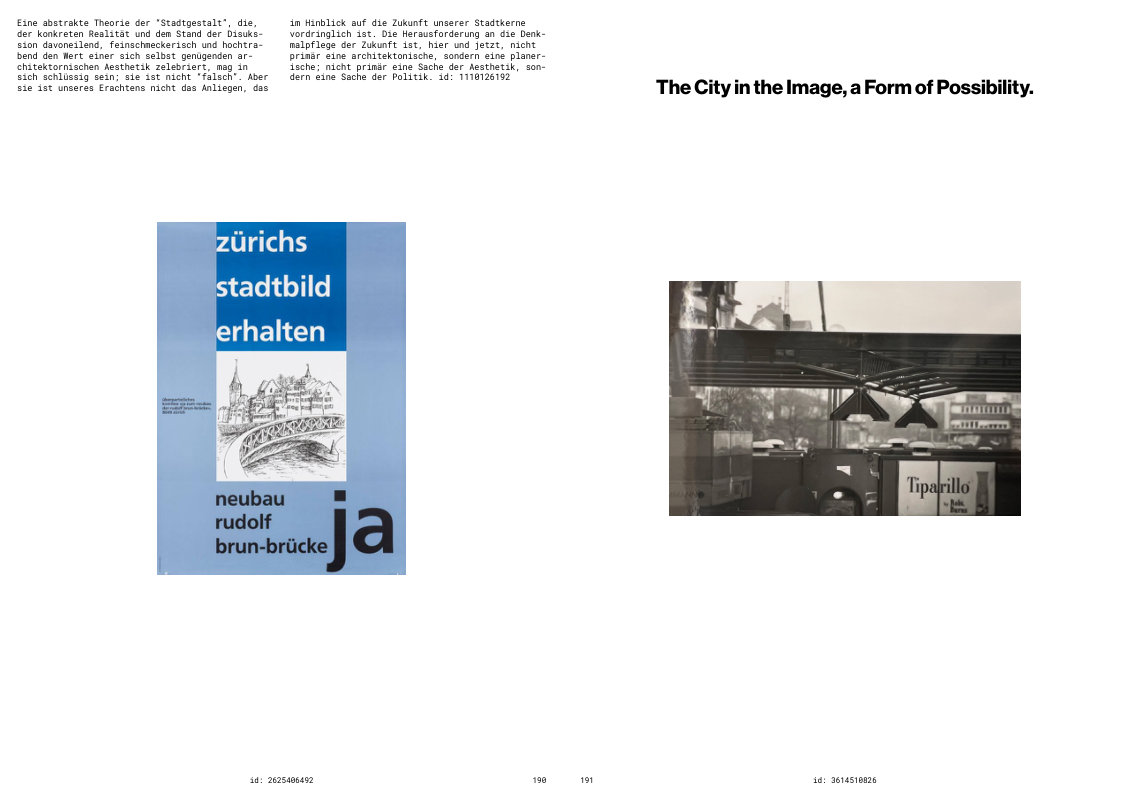

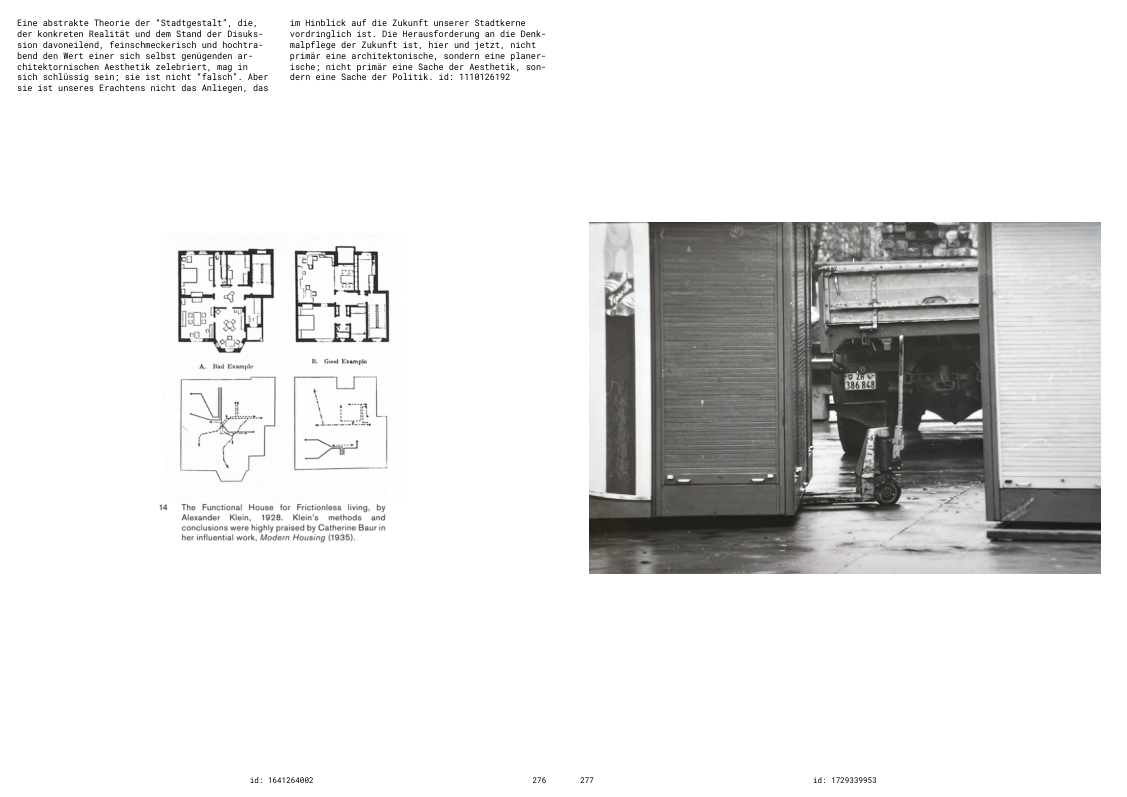

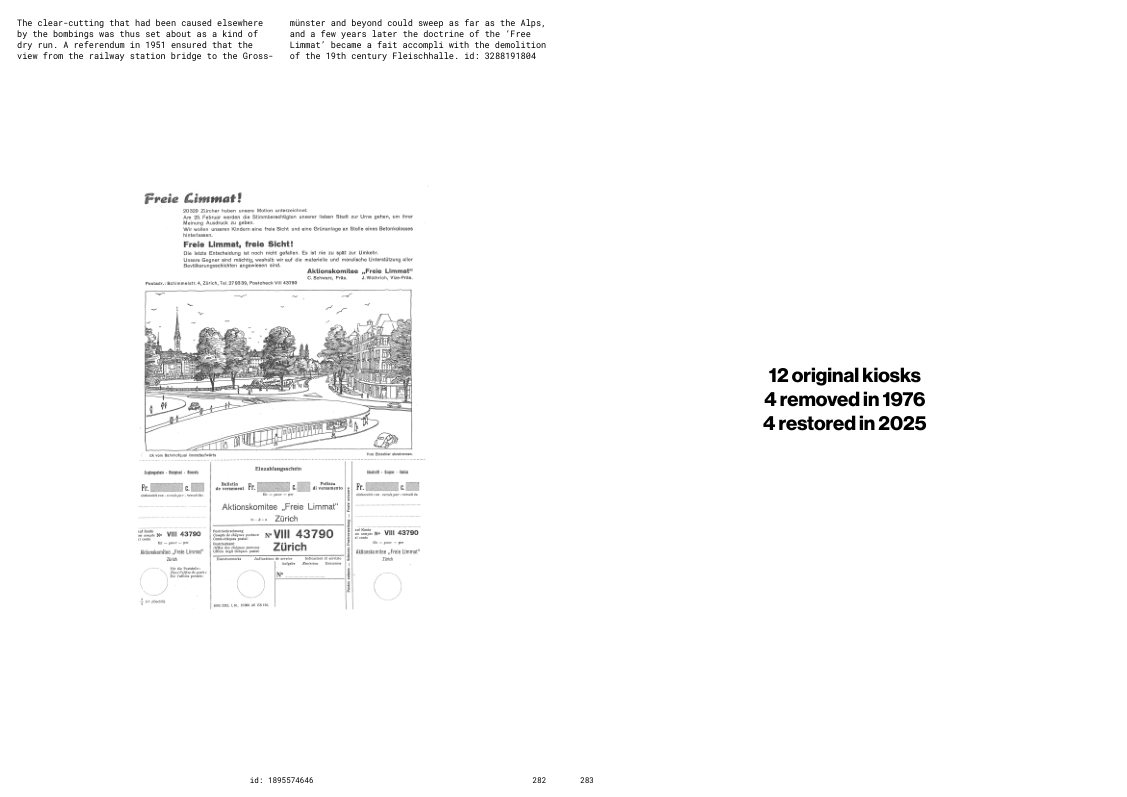

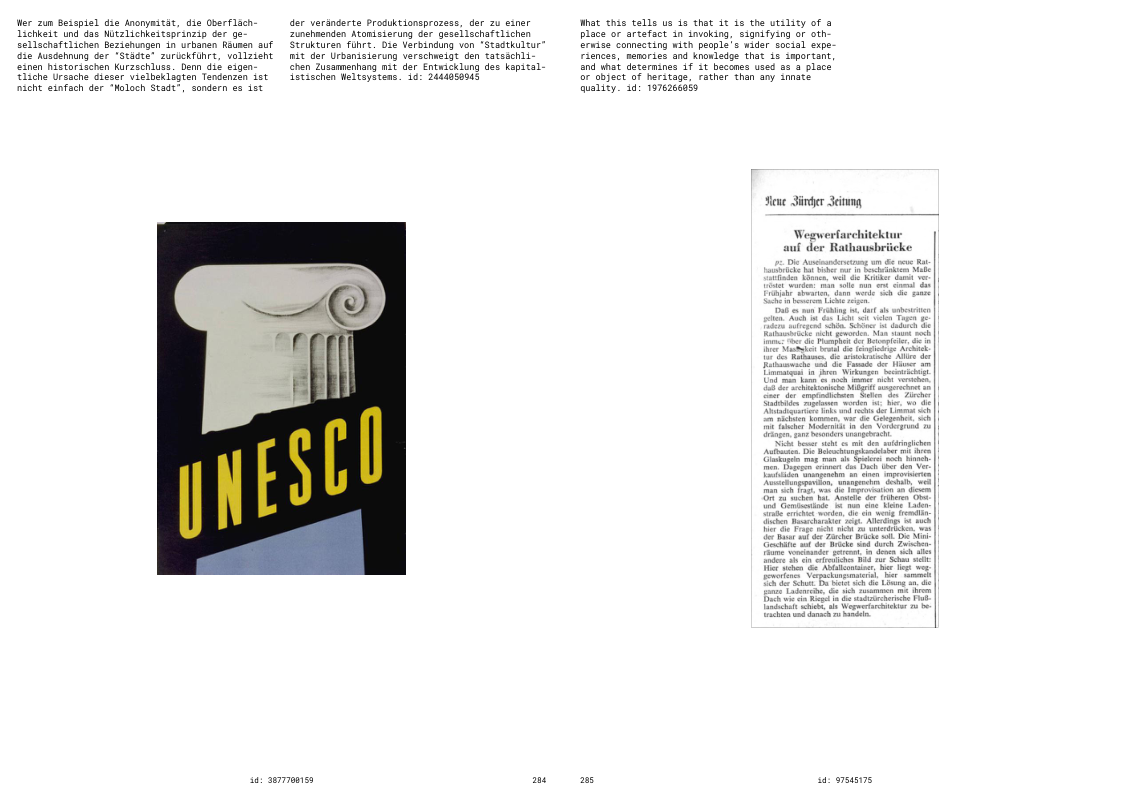

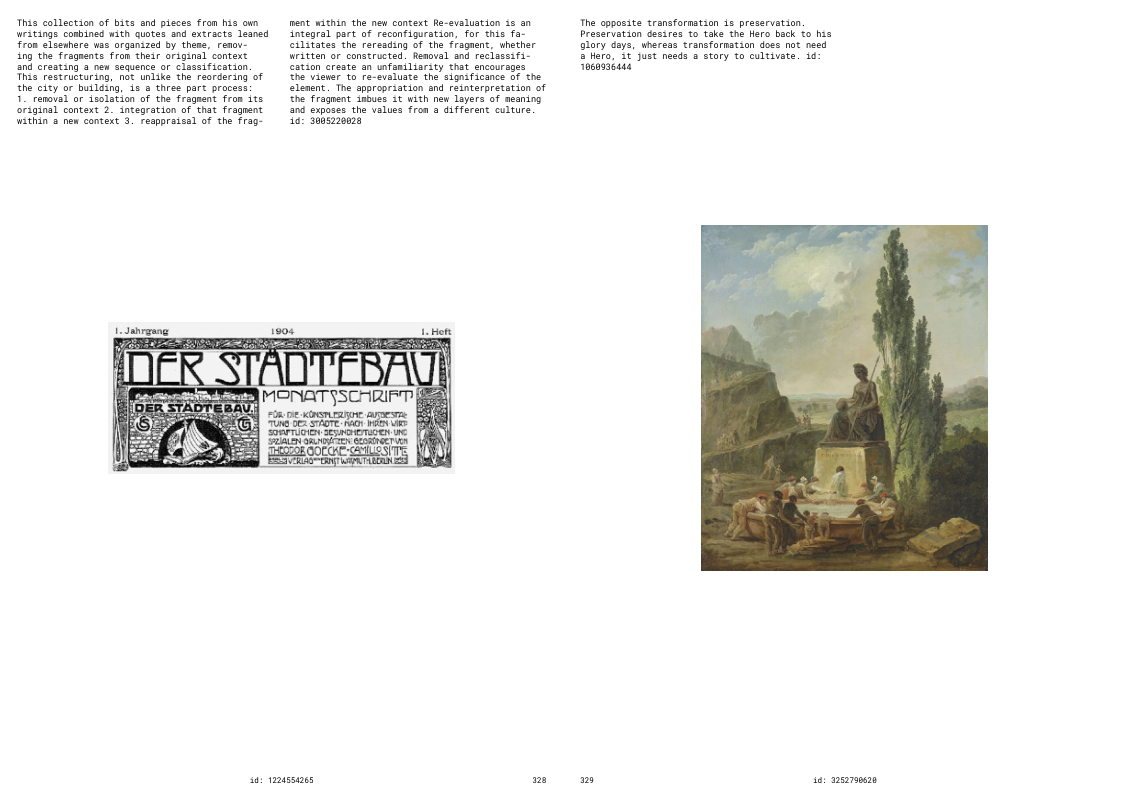

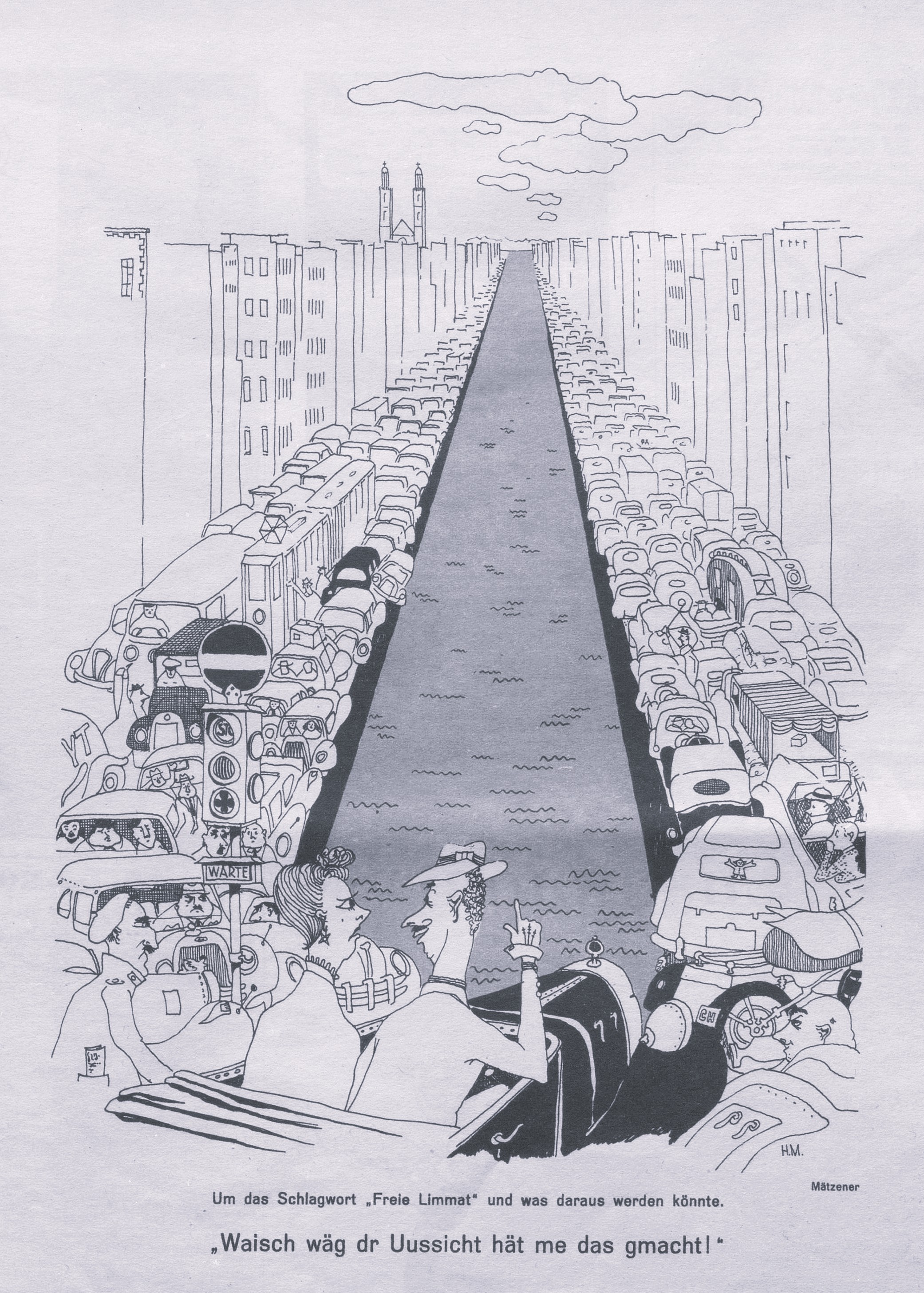

Part of our task is to demystify this technocratic vocabulary, to expose how measurements and models come to carry the weight of cultural ideals, how they reproduce a vision of the city as legible, governable, and smooth. It is a curious historical symmetry that today’s calls for demolition are justified through hydraulic calculations, when seventy years earlier, during the campaign for the Freie Limmat in the 1950s, similar interventions were legitimated in the name of the panoramic view. Then, too, structures along the Limmat were dismantled under the pretext of water management, but what truly flowed was an aesthetic ideology, one that sought to liberate visual access to the river.

The shift from scenic to technical argumentation suggests not a rupture, but a transformation in the language of control. In both cases, the river becomes the canvas for projecting a particular urban imaginary. first visual, now procedural, each time shaping what is allowed to remain.

COSMOSCOPE

COSMOSCOPE